“All strippers take cash!” Laura Goetz grinned. Her class burst into laughter—in the awkward sort of way you do when you’re too stunned to respond with words. “I mean calculus. They need it ‘cause they’re always spinning around those poles.” No, Ms. Goetz wasn’t giving life advice about exotic dancers. She was instead teaching trigonometry to sophomores in Richard Montgomery High School’s rigorous International Baccalaureate magnet program. When given an angle in a specific quadrant, the first letters of her mnemonic help students determine the sign when inputted in the sine, cosine and tangent functions.

The original mnemonic, “All students take calculus,” has been revised because what better way is there to teach trig memorably than making her class giggle at an innuendo? All her lessons are filled with crazy stunts like this. When she’s in the classroom, she’s an uncontained ball of energy—gesticulating, shouting, cackling and constantly beaming—somehow capturing the attention of a roomful of teenagers.

Over the span of two months, we interviewed Ms. Goetz in a series of after-school conversations. We also spoke with her colleagues and both her current and past students. During our first conversation, Ms. Goetz sat at her desk in her office chair. Her fashion taste is modern—you can often find her in a pair of bright white Air Force Ones—and her outfit was elegant and striking. She speaks very animatedly, and no matter the seriousness of the subject, she often uses jokes and sarcasm to lighten the mood. During our interviews, she went on entertaining side tangents, not unlike how she’ll often branch off into personal anecdotes during a lesson.

Ms. Goetz landed her first job teaching at Richard Montgomery in the fall of 1994. She’s become a permanent fixture of the department, even as the years crept by and the way math was taught transformed. The TI-84 was developed in 2004 and is now the standard calculator in classrooms across the globe; Sal Khan created Khan Academy in 2008 which now has 2.1 billion cumulative views; Desmos, the online graphing calculator, was released in 2011 and made higher level math more accessible than ever; and in recent years, generative AI entered the hands of everyday students. Her teaching has adapted alongside these innovations, but at her core, she’s stayed the same passionate, radiant person throughout all her 30 years.

Laura Denise Committe was born on Jul. 22, 1961, in Bowie, Maryland, to David and Joan Committe. She was a child of the seventies—a decade of bell-bottoms, platform shoes and afternoons with Casey Kasem. Her evenings were spent practicing softball, volleyball and gymnastics, but even with such a busy schedule, she was still very extroverted and popular. On the weekends, she was always with her friends on bike rides, hiking near the creek by her house or roasting hot dogs during bonfire nights.

In high school, Ms. Goetz says that her grades were always stellar, and she dismissed any notion of being an average student. “Math came easily to me, and my friends were always asking me for help,” she said. She says that all her friends took “lunkhead classes” while she enrolled in “nerd” ones. Instead of studying, those friends were often sneaking out for parties. But it was at one of those parties where her life was changed forever.

One day, during a party in the fall of 1979—one where she says all her friends were “drinking themselves stupid, puking and smoking a bunch of dope”—Ms. Goetz met “Josh” (she requested that we not use his real name). Josh was a charming and handsome teen, and they struck up a playful conversation under the party lights. Soon, they began dating. 10 months into the relationship, Ms. Goetz became a teenage mom. Previously, she had dreamed of studying at the Air Force Academy to become a pilot. “I still wish I could fly a plane,” she sighed. “But being pregnant and 17 kind of put an X on any of those plans.”

At the time, Josh was two years older than Ms. Goetz and was attending the University of Maryland, so he sent her to the health clinic for a free pregnancy test. When she tested positive, the woman who administered the test advised her to terminate. “She didn’t even ask if I was going to keep the baby. She just assumed that I wasn’t… And she said, ‘Why ruin all these lives? Your life, Josh’s life, your parents’ life, his parents’ life?’” she said. Ms. Goetz took this counsel, reflected and decided against taking the “the easy way out.” “Why should one life pay because of a decision I made? I need to be responsible… I just came out of there and I said to [Josh], ‘I cannot terminate this pregnancy.’”

Dean, her first son, was born on May 7, 1981, and she got engaged to Josh the same year. “I was in love, and it was gonna be forever,” she said. But Josh didn’t quite feel the same. The glamor of their teenage love faded as the reality of adult life as young parents sank in. At one point, he told her he wasn’t sure he wanted to marry. “And I freaked out,” she said. “He didn’t know how to deal with it. And so he just shut down.” They decided to continue with the marriage anyway, and the ceremony was on July 4, the same year. But after that incident, Ms. Goetz began to notice more of Josh’s concerning behavior. “I hated the way he talked to his mom. He talked down to her, he talked mean, he told her to shut up. I never would talk to my parents that way. And I remember saying to him one time—I can still see us walking outside, near the side of his house—‘You’d never talk to me like that. Right?’”

The abuse began, according to Ms. Goetz, when she had her third child, Drew, in 1987. The pressure from Josh’s dissatisfaction with his career, financial struggles, and three young children culminated in explosive arguments during which he took his frustration out on Ms. Goetz. Under the stress and anger in those moments, he couldn’t manage or calmly articulate his emotions. First, the abuse was verbal. Josh would try to tear her down with names and swears. But that wasn’t enough. It soon turned physical, though he would never do it in front of their children to preserve the veneer of the perfect father.

During this time, Ms. Goetz was attending night classes at Montgomery College. She planned to become a teacher temporarily so that she could spend the summers with her kids and then quickly switch to a better job—she was sure that “being a teacher is probably the worst thing ever.”

One night, Josh beat her during an argument. One blow pushed her jagged earring against the side of her head and cut her. Ms. Goetz’s college linear algebra test was the next day. “I went to itch my head right here,” she said, pointing underneath her ear. “Dried blood fell on my test from the cut that had scabbed over. I did start to cry, but then I had to stop, because I had a linear algebra test to finish.”

Ms. Goetz paused in our interview as she sat at her desk, hands and legs crossed, and shoulders shrugged. School had already ended, but in the back corner, there was still a frantic student whose test corrections were due that day. No matter when you walk into 324, you’re always likely to find a stressed student drilling math or asking Ms. Goetz questions. That afternoon, Ms. Goetz wore a pensive countenance. As she recounted the abuse, her voice was crackly and her usual enthusiasm slightly muted. “I try to bury most of it,” she sighed.

She does recall that one time, Josh was so enraged that he pushed her down the stairs, waking her son Dean up. Ms. Goetz quickly ran up and comforted her son. “Oh, Mommy’s so silly. She just tripped,” she hugged him. “I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to scare you.”

There was only one time Ms. Goetz ever tried asking her parents for help. After a particularly bad fight, she sought refuge at her childhood home. When Josh knocked on their front door and apologized to her father, David Committe simply accepted his apology instead of defending his daughter. To him, an abuser who shared his Catholic beliefs, even if in name only, was preferable to a divorce. “I watched my dad shake his hand. The hand that hit his daughter,” she said. “It took me a long time to forgive my dad for that.”

Eventually, things got so bad she prayed, asking God a question: If He was so loving, why did He let Josh abuse her? She heard Him respond, “I’m here.” Things didn’t get better, but God’s presence comforted her. “Still had to survive, still had to get through the next day, still got hit again, but He was there.” Today, though she questions some Catholic doctrine, Ms. Goetz says she accepts the church for all their flaws. “Do I think Jesus was born on Dec. 25 under a star? I don’t know. But I don’t care about that part,” she said. “During abuse, where I was at my worst, feeling the worst, I felt God’s presence when I really needed it.”

The main reason she says she endured the abuse for so long was financial. Without Josh’s support, she was afraid she wouldn’t be able to continue school. “The only way out was to finish my education,” she said. “Getting my education was going to free me and allow me to take care of my kids.”

However, it was not Ms. Goetz who walked away from the union. In 1991, Josh filed for divorce. “I was powerless at that point. I didn’t have any money, so I couldn’t get a lawyer. I tried to get free representation, but it was hard for me to navigate. So he got a lawyer, and he drew it all up and I just signed it,” she said. “Wasn’t the smartest thing to do. I signed away all rights and any pension.”

In the process, there was only one concession that she wrung out of Josh: He had to tell the kids about the split. “I said, ‘You have to tell your children. I will not do that for you. You have to tell them that you’re moving out.’” And so one day, he told them to follow him into the basement. Ms. Goetz stayed upstairs, choosing not to witness such a devastating scene.

Josh drew up the legal documents for their divorce in a way that made it possible for him to pay the bare minimum child support—even so, he’d always make late payments that didn’t even cover food expenses. To both continue college and feed her children, Ms. Goetz was forced to go on welfare for two years. “I got food stamps, so I had to go to the grocery store and stand in line, and it is quite obvious that you are not paying with money,” she said. “Other people had to do it. Other people had it worse than me. But it was certainly nothing I had ever envisioned.”

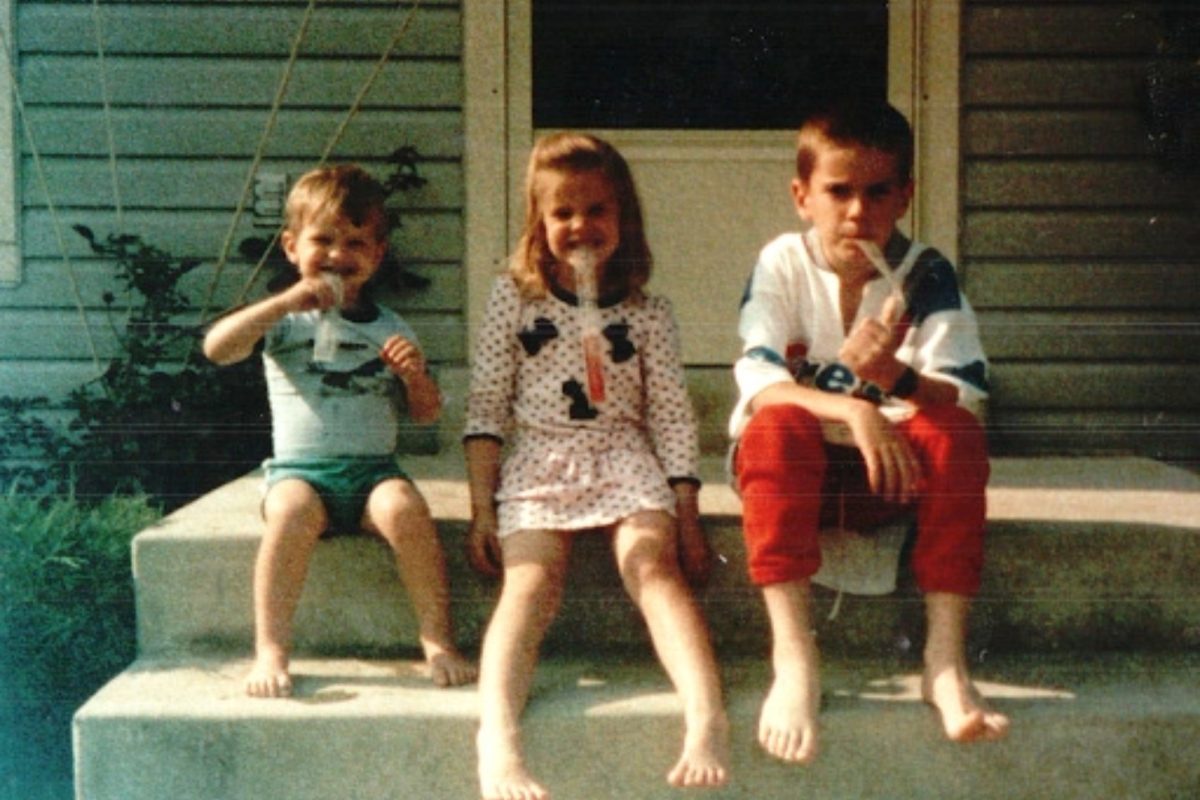

Ms. Goetz continued to work towards a better career, and in 1992, she transferred her credits to Hood College and began working towards a math degree. At the start of her day, she would wake up at two or three in the morning and do her homework before cooking breakfast and getting her kids ready for school. During the school day, she either attended classes or went to work at her part-time jobs as a babysitter, bank teller and a receptionist at a doctor’s office. Then, her kids would arrive home and she would play with them, cook and clean. After an exhausting day, she would finally put them to bed, though occasionally, she would still have to attend night classes. But she never complained. “I went home to those kids and looked at them, and they did not deserve a sad mother. They didn’t deserve a mother who was crying,” she said. “They deserved a mother who was going to make them peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and play with them in the yard.”

Josh was still in their lives peripherally, sometimes showing up for his weekend visits. And when he didn’t, Ms. Goetz had to cover for him to spare their children from disappointment. “I’d lie to the kids and say, ‘Oh my bad. He told me he wasn’t going to come.’ The kids had enough to deal with. They didn’t need to be mad or resent their father,” she said. Her silence was the most difficult during her children’s teenage years. “They wanted to go with him because he didn’t make them do their homework, and he took them to McDonald’s, and he never disciplined them,” she said. “They were mad at me and yelling at me because I was mean, and I made them do their homework, and I made them do chores.”

To this day, Ms. Goetz has never had a conversation with her kids about what she endured, and she says she never will. “He never did it in front of them so it was easy to hide,” she said. Of course, when they grew up, her children pieced it together, though they still don’t know the details. “It was not easy to not say, ‘Do you know what a scumbag your dad is?’” she laughed. “But I didn’t, and as a result, they are healthier people and I’m proud of that.”

Without her children motivating her, she doubts that she would have persevered through all the abuse. “But I had three people who didn’t ask to be brought into the world that depended only on me because their dad let them down,” she said. “I was not gonna let them down, so I took the sucker punches. Took being pushed down the stairs. Took the verbal abuse. Till I got my degree.”

In 1993, Ms. Goetz was hired as a student teacher at RM. Her grandmother, Ella Morgan, offered to live with her for those four months to take care of her kids while she was at work. For the first time, Ms. Goetz opened up about her abuse, “woman to woman,” and likewise learned about Morgan’s past. In Morgan’s marriage, her husband regularly abused her until he eventually committed suicide when Ms. Goetz was a teenager. “I became much closer to Ella. I still credit her with so much of my outlook on life. Where I am is very much due to her,” Ms. Goetz said. “I was like, man, I have it bad, but there are plenty of people, and here’s my grandmother that has survived and is a loving person and a kind person and a happy person.”

When Ella passed away in her 90s, Ms. Goetz was hit with a wave of grief, even after doing all she could to strengthen herself in anticipation. “Life isn’t permanent, and I made it a point to make sure that I saw her, talked to her, called her, visited her,” she said. “I made sure I told her how much she meant to me and the impact she had on my life. So it wasn’t a shock when she died, but I was sad and I missed her. I still miss her. I think about her all the time.”

Finally, in May of 1994, Ms. Goetz graduated from Hood College and was given an open contract at RM that fall. “I don’t know that anyone felt better or freer than I did when I got that degree,” she grinned. “And then it turns out teaching is awesome, and I love teaching, and I love what I do, and I get a lot of satisfaction out of it. I believe that I make a difference in some kids’ lives, and I have never looked back or regretted becoming a teacher since.”

On Ms. Goetz’s first day as a full-time teacher at RM, she met Charles Jon Goetz III (who goes by Jon) in the cafeteria of the school. All the teachers were doing a “mind-numbing icebreaker,” taking personality tests that would assign them a color based on their characteristics. “I had noticed him coming in, and I was like, oh, he’s kind of cute,” she said. Ms. Goetz was assigned the orange group—which had the trait “You see what you want and you go after it,”—but Mr. Goetz was put in the blue. She read her trait, lied, said she was blue and took a seat next to the man she would spend the next 30 years of her life with.

The fall of 1994 brought five new teachers to the school. Along with Ms. Goetz were one other math teacher, a history teacher and two new physics teachers, one of whom was physics teacher Mr. Goetz. The group of five quickly bonded and became friends outside of work; many evenings after school were spent hanging out at happy hour, playing flag football with their students and attending baseball games. Today, of the five, only Ms. and Mr. Goetz remain at RM.

By May of that year, Mr. Goetz had broken up with his college girlfriend, and so he asked Ms. Goetz out to see a movie. Ms. Goetz, also being a “history nerd,” wanted to see “Braveheart,” a historical film about an invasion of England. “So not your typical rom-com,” Mr. Goetz laughed. “I was like, ‘Okay! this is going well already.’”

By the end of their second year as teachers, they started dating more seriously and were engaged the next spring. “We got engaged very casually,” Mr. Goetz said. “We were casually at our house, and I asked her, and she said yes.”

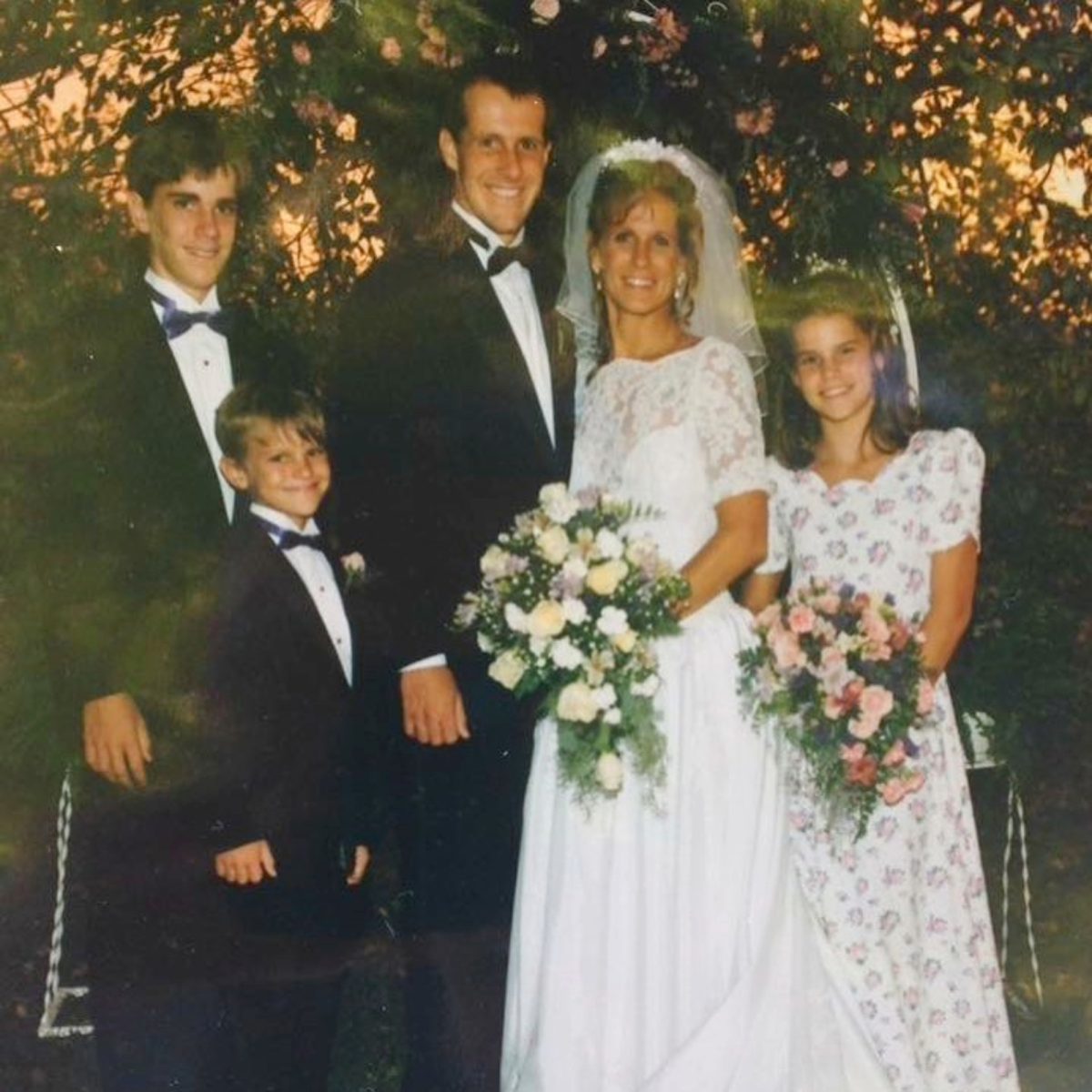

Ms. and Mr. Goetz got married in Kent Island on Friday the 13th, in September of 1996. The couple had been searching for ways to save money and discovered that the unlucky day was discounted; other couples were too afraid to book it. As they were both “not superstitious,” they reserved it and went ahead with wedding planning. “We didn’t have a wedding planner. We wrote our own invitations because we didn’t have a lot of money,” Mr. Goetz said.

A pair of girls named Charissa and Kristen were the only students present at the wedding. At the time, the two were taking Ms. Goetz’s Related Math, a class for students struggling in Algebra 1. They were “giggly, hard to keep on task, but really fun,” Ms Goetz said, and loved watching the couple when Mr. Goetz would come over to help teach during his breaks. The couple would follow each other around as they answered questions, stealing teasing glances at each other and smiling sweetly when their eyes met. The day after they got engaged, Ms. Goetz wore her wedding ring. “I was coming around checking their work, and they were working on something, and I just put my hand down like this,” Ms. Goetz said, slapping her hand on her desk. “And they went, ‘Ahh!’ and they screamed and they were just so, so, so happy.” Charissa’s father, a minister at a church in Rockville, was the one to officiate the wedding.

However, her father, David Committe, was so unsupportive that he refused to attend. He believed his daughter was committing a grave sin—in the Catholic Church, divorce was frowned upon and remarriage was prohibited, and besides, Mr. Goetz was a Protestant. Even though Mr. Goetz treated Ms. Goetz infinitely better than Josh, Committe was blind to everything but the fact that such a marriage wouldn’t be moral in the eyes of the church. But at least, Ms. Goetz says, she didn’t have to worry about his judgment and hate ruining the happiest day of her life. After the marriage, he stopped speaking with the new family and removed himself from his grandchildren’s lives.

Despite her father’s disapproval, Ms. Goetz has no regrets about marrying a man who treats her “like a princess.” She says that she loves Mr. Goetz—he is fun, compassionate, kind and funny—and “when I look at myself through his eyes, I see someone better than I really am.”

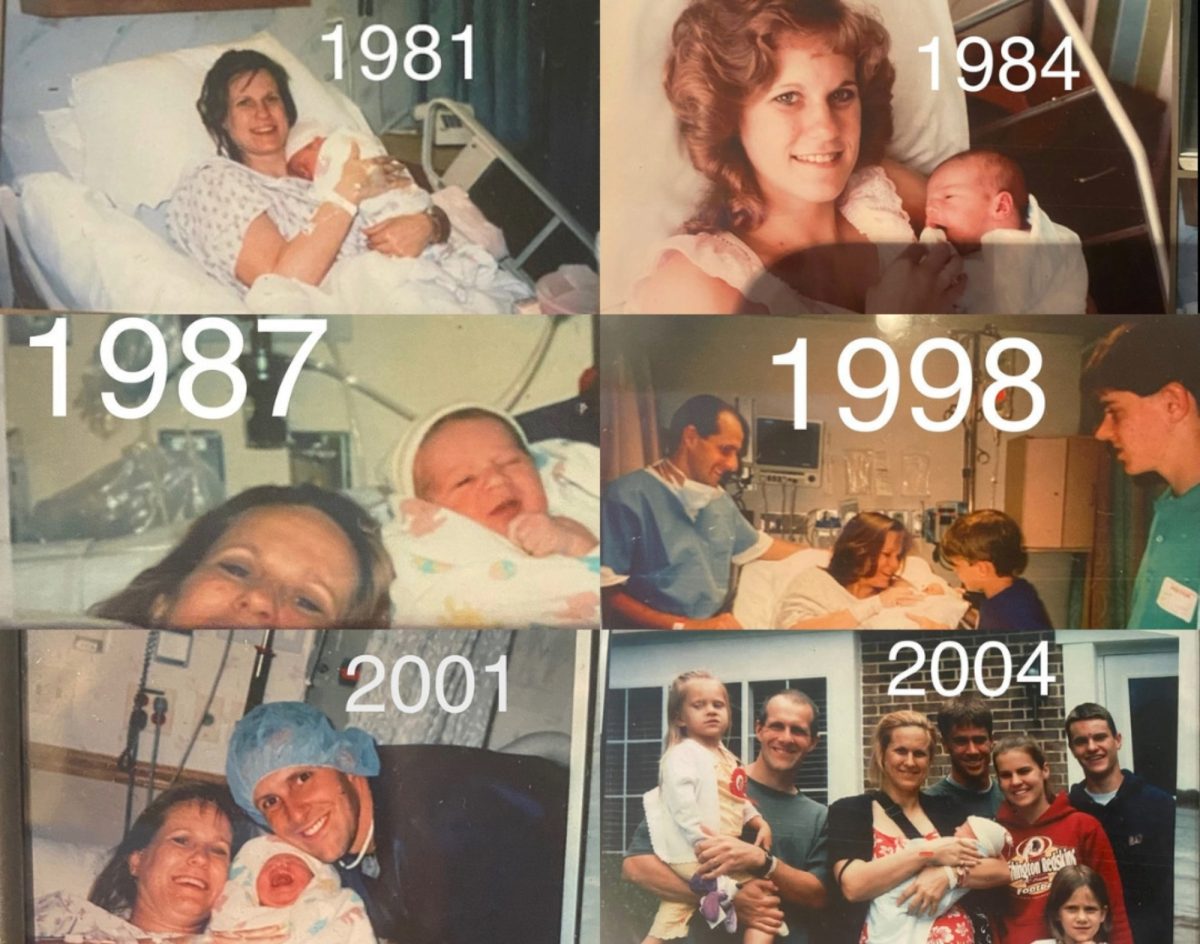

Mr. Goetz quickly stepped into the role of the caring father that Ms. Goetz’s first three children needed. “When we first met and the romance was beginning, people were like, ‘Wait, you’re dating a woman with three kids already? Well, how is that?’ Well, they’re great kids. So that worked out well because had they been bad kids, I’m not sure what would have happened,” Mr. Goetz chuckled. “I got along with them right away… I don’t call them my step kids. I call them my kids. ”Mr. Goetz had three more kids with Ms. Goetz: Devon in 1998, Delaney in 2001 and Dylan in 2004, continuing the tradition of D names.

Throughout our interviews, Ms. Goetz only said one positive thing about Josh: That he had stepped aside for Mr. Goetz, letting him take his place as the father figure. “The best thing [Josh] ever did—I will always give him credit for this. He realized, on some level, when Jon came into our lives, that Jon was going to be able to give his kids things that he couldn’t. He never made the kids feel guilty for counting on Jon or for loving Jon,” she said. “When my oldest daughter got married, both Jon and [Josh] walked her down the aisle.”

Today, Ms. and Mr. Goetz have spent half their lives married. Mr. Goetz says their memories are unique because they’ve been colleagues for so long. “We know a lot of people, so it’s more like a family than a place of work,” he said. “I have memories of driving in every morning—talking about what we’re doing the next day, what we’re doing today and what we did that day on the way home.”

In school, the two sometimes pop into each other’s classes to scare each other. Once on Valentine’s Day, Mr. Goetz surprised her in the middle of a lesson with a giant bouquet. They also dance together in many of the school events and assemblies. Yolanda Li, junior at Georgia Tech (who was Ms. Goetz’s student for all four years), says she remembers how, during a pep rally, the two cartwheeled off together after performing the “Jingle Bell Rock” dance from “Mean Girls.”

Once, when they were still young teachers, they skipped school together. Mr. Goetz is a New York native and huge Yankees fan, so on the day the Yankees were playing the deciding World Series game against the Padres, the Goetzes called in “sick.” Their older kids were attending RM at the time, so they dropped them off at school, took Devon (who was a baby) and drove the 200-some miles to New York City to meet with Mr. Goetz’s dad, where they watched the game and the ensuing parade.

Around the same time, they had a rivalry with the students they played against in the staff-student football games RM used to hold. One winter, one of the students hit the two with snowballs in the parking lot. “Well, we’re gonna get him back. So we had someone go into the class and say, ‘You’re needed in the office, come out in the hallway,’” Mr. Goetz said. “Then we threw snowballs at him in the hallway and then ran away. Of course, he didn’t report it, because he had hit us with snowballs the day before.”

Ms. Goetz was sitting at her desk, recounting more stories of Mr. Goetz with us, when he interrupted, coming into her class to help her find something she had told him she had lost. Without even “[having] to think about it,” Mr. Goetz told her to check to see if she had it on her. She reached into her coat pocket and found it.

“He’s so smart!” she giggled, like a fourteen-year-old with a crush.

“We’ve been married a long time,” Mr. Goetz sighed, pretending to be exasperated. “I could already predict it.”

The two have the same energetic personality, which Mr. Goetz says was what first stood out to him. “I immediately thought she was a super fun person and also pretty amazing, because she was a single mom, raising three kids and teaching. Aside from being fun and positive and being a nice person, she also worked super hard,” he said. “That’s pretty much what you get in the classroom. This passionate person who is living life fully and doesn’t get bored.”

(Photo courtesy Laura Goetz)

Ms. Goetz has taught all her children except for Dean, and Mr. Goetz has taught all but Deanna. On all their kids’ birthdays, the two would go into their classes to sing Happy Birthday. “I loved teaching my kids.” Ms. Goetz laughed. “I don’t know that they loved it, but I loved it.” Ms. and Mr. Goetz would often randomly visit them in their classes during their breaks. “When they would forget their lunch,” Ms. Goetz recounted, “I would wait for them to be in a class, and I’d go in and I’d say, ‘Honey, you forgot your lunch. Mommy brought you your lunch. Here you go. I love you, love you, love you.’ And everybody would laugh and embarrass them.”

Most of all, Ms. Goetz says that she enjoys watching her kids learn. “I love to watch all my students learn. I love to watch all my students’ aha moments. But when it’s your kid, it’s even more special,” she said. “They were very good students, and when I graded their papers, they were doing great, and I was just so proud.”

All six of the children inherited their parents’ passion for STEM—all graduated from the magnet program, four attended MIT and two attended Northeastern University. Dean majored in electrical engineering and is now the vice president of an electrical engineering company in San Diego, where Delaney works as a mechanical engineer. All her other children majored in mechanical engineering.

As for her father, David Committe continued to remain distant after the Goetzes’ marriage, but in 2012, he once again felt compelled by his religion to interfere. One of her sons got married to a Jewish woman on Oct. 13, 2012, in a ceremony presided over by a rabbi. It was a joyous and peaceful gathering, and the couple was completely in love. But Committe was so upset at the thought that his grandchild—even one he had cut off—would marry a non-Christian that he wrote the newlyweds a vitriolic letter about how they were “going to hell” for their sins and, just like 16 years prior, refused to attend the wedding. Committe had promised to drive her mother, Joan, who wasn’t capable in her old age, but on the day of the wedding, he reneged to physically block her from attending. Ms. Goetz finally lashed out. “He came after my kid. And, I mean, my kid was 25 but it doesn’t matter. He went after my kid. I let him have it,” she said. “I said, ‘You are keeping yourselves out of our lives. You are keeping my mom out of our lives. It’s sad, and I feel bad for you, and you’re missing out’… and so I stopped reaching out.”

For many years, it was difficult for Ms. Goetz to let go of the resentment that had built up over the years of disapproval and desertion from her father. She was angry—that he forgave Josh, that he didn’t attend her wedding, that he cut off his own grandkids and that nothing, not even his own daughter’s happiness, seemed to matter to him more than the rules of his religion. But gradually, as her mother’s dementia progressed, Ms. Goetz began to communicate and visit her parents again. Remembering the violence her father endured in his childhood helped. Committee’s father, Chester, was an alcoholic who beat both his wife and children. One time, he was so enraged by his wife in an argument that he took a knife, grabbed his son and threatened to kill him if she said another word. His abuse continued until his sudden suicide when Ms. Goetz was six. “Usually kids from abuse are also abusers. My dad did not hit my mother. My dad did not hit us,” she said. “He was emotionally not there for us, but he was such a better father than his father was.”

According to Ms. Goetz, the most essential part of finding forgiveness was reflecting on her own parenthood. “I’m not a perfect mother. I’m not a perfect person. I’ve made mistakes, I’ve said things that I regret in anger. I’ve done things I’ve regretted—never to that level—but still, I want my kids to remember the good things that I’ve done,” she said. “It took me many years to forgive, but the anger and the bitterness that I felt didn’t change anything and only made me feel bad. Letting it go didn’t change anything either, but it made me feel better. And in the end, I think that’s what whatever God there may be would want.”

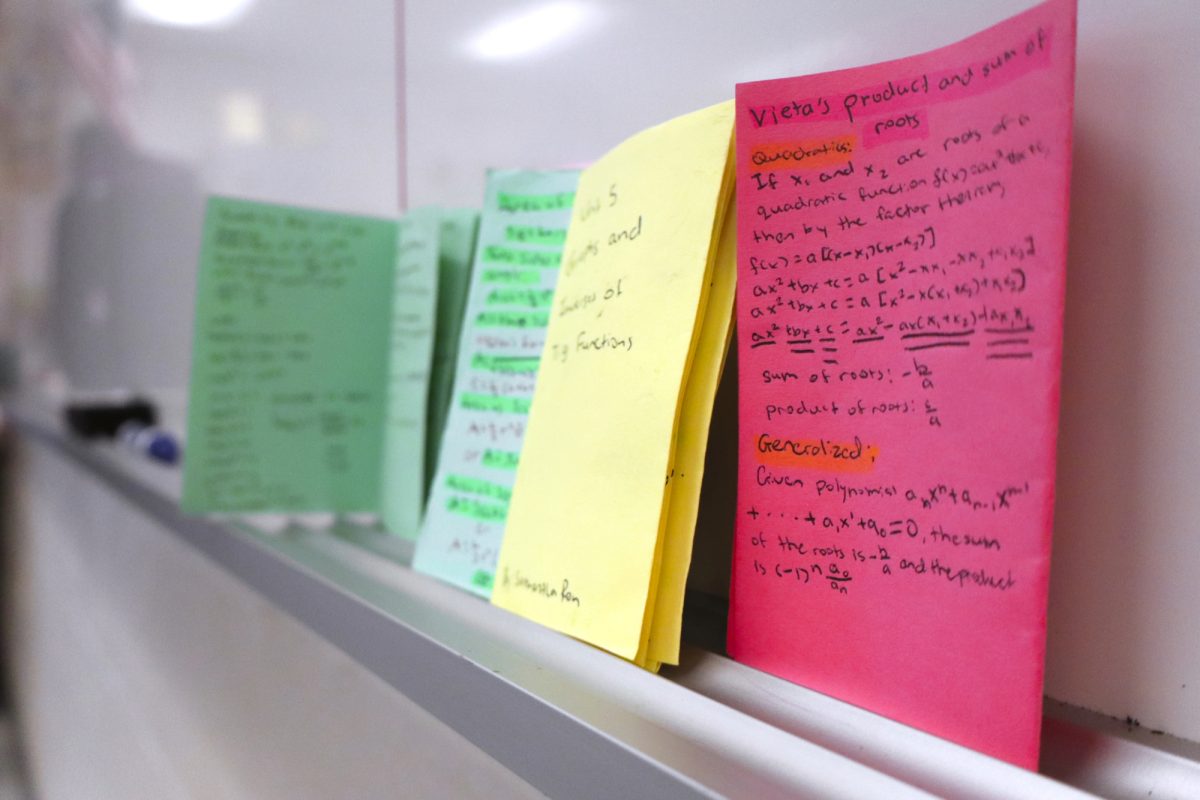

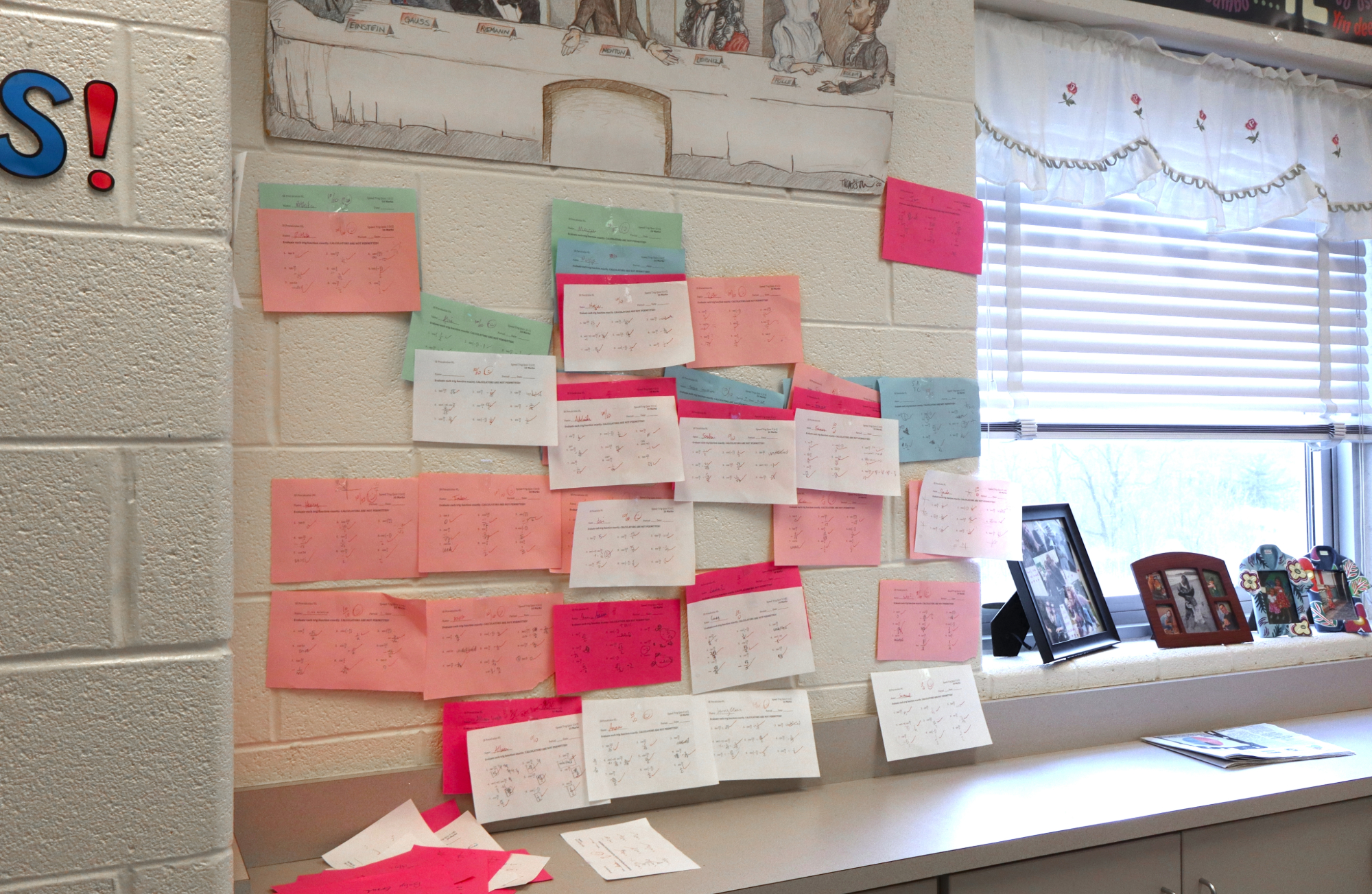

Room 324 was unusually quiet. It was the first day back from break, so by the time students reached their last-period math class, they were much too tired to pay much attention to Ms. Goetz’s excited shouting over some new trig identity to memorize. The big hand of the clock above the doorframe inched closer to six—only five more minutes till the bell. But suddenly, Ms. Goetz stopped talking. Her students’ faces followed her hand as it extended to point upwards. “Wait,” she grinned. “What’s that hanging from the ceiling over there?” Something small and pink was poking out from the corner of a ceiling tile. Her students groaned as the room erupted into a clangor of students scrambling to align their desks in testing position, put away their notes and get out a sharpened pencil. Knowing Ms. Goetz, there could only be one possible explanation. Ms. Goetz strode across the classroom to the desk under the panel and climbed on top in one swift step. She knocked the panel aside, and a shower of tiny half-sheets of colorful speed-trig papers came fluttering down. “Happy. Frickin. New Year.”

Speed trig is a mathematical skill taught in a precalculus course. For the special angles, 0°, 30°, 60° and 90°, there is a corresponding exact value that can be obtained when inputted into trig functions such as sine, cosine and tangent. Memorizing those values is essential to solving problems, especially in later courses like calculus—in a way, it is much like the elementary-aged days when your fourth-grade teacher would drill the multiplication table, only now it’s more abstract and harder to grasp. The math department achieves this memorization using a series of speed trig pop quizzes that are randomly scattered throughout the trigonometry units.

In an honors class, students are given five minutes to solve nine problems, but Ms. Goetz teaches magnet IB HL precalculus, so her students will start with only three minutes. Only 90 seconds remain by the time they reach their sixth quiz. Being the teacher she is, she tortures her students by inventing creative methods to surprise her kids in the middle of class with speed trig announcements. Some of her favorites include having Mary Ayala, one of the school secretaries, announce the speed trigs over the PA system, and having Mr. Goetz scare the students and jump in the middle of the lesson with a booming thunder stick. Because those dreaded colorful half-sheets can be brought out at any moment, her students are forced to spend hours drilling to prepare.

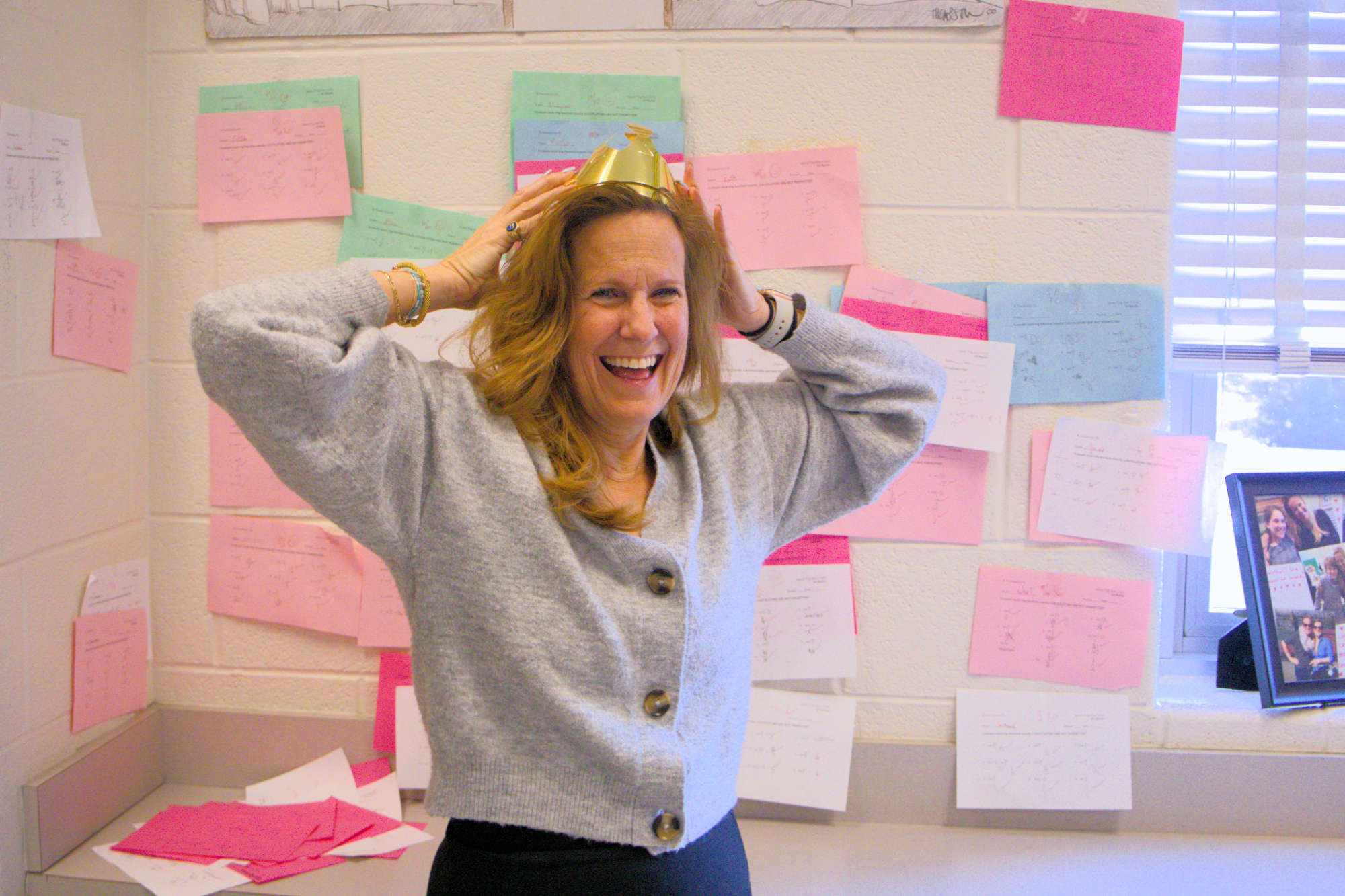

The promise of glory—though the type only enticing to the magnet teens she teaches—also motivates them to study. Ms. Goetz has a stockpile of paper crowns in her closet, and the student who has the best speed trig average at the end of unit six is crowned the “Speed Trig Queen.” (“Usually Queen,” she smirked. This year proved her right, failing to produce a single king).

Some students do grow to appreciate the surprise. “It made the class more exciting because you never knew when speed trig was gonna come,” junior Malena Martin said. “Even though in the moment it was like, ‘Oh gosh, I have to study so much for speed trig.’ I remember every single [speed trig value] to this day.” And eventually, the seemingly needless stress does pay off, no matter how brutal Ms. Goetz’s methods may seem. “I hated it at first, but honestly, I’m so grateful for it. I’m so grateful for speed trig. It has helped me so much,” sophomore Mouna Dantata said.

Emily Wu, a junior at USC and a former student, recalls how once, her class forced Ms. Goetz to take one of her own detested speed trigs and, remaining true to Ms. Goetz’s style, the paper was hidden at the bottom of a gift bag. “We were like, ‘We got you a gift, Ms. Goetz,’ and then she pulled it out and it was a speed trig and we were like, ‘Go, go, go! You have a minute!’ and then we started timing her,” Wu said. “She went along with it, and she actually finished the speed trig in a minute. I think that’s something I really love about her—she’s very much willing to engage with her students.”

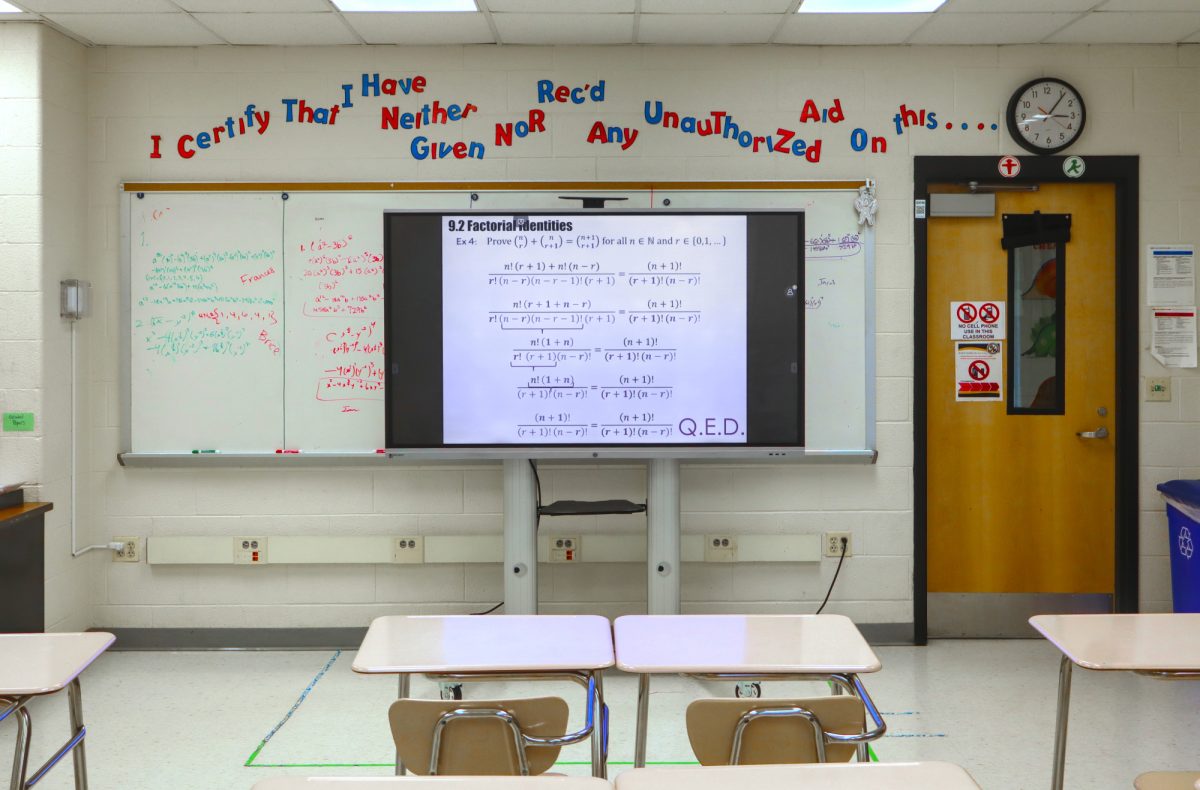

In the beginning years of her career, until statistics was introduced to the department, Ms. Goetz taught every single math class offered. During this time, she helped develop the objectives and curriculum for magnet algebra two (known as AAF) and magnet IB HL precalculus, which are still in use today. Then in 2001, she became the resource teacher, so for the next 18 years, she only taught AAF and AP BC calculus. However, when she left the position in 2019, she switched to teaching HL precalculus, BC calculus and multivariable calculus, which are among RM’s most rigorous math courses. “I have now been teaching the same kinds of classes for multiple years in a row. I do think it takes that to really become an expert at it,” she said. “I think that that is good for me, it’s good for the kids.”

Ms. Goetz says she’s happy teaching her current classes because the external AP, IB and multivariable exams allow her to be creative. “That’s what IB and AP tests do. ‘This is what we’re going to test them on. At this point, get them here.’ And then I’ve got the freedom to design, ‘How do I think it is best to get them there so that they’re successful when they get there?’” she said. Ms. Goetz creates her own lessons, homework and quizzes, and she’ll adjust them annually to prepare her students better. “Every year I’m looking at those tests and those rubrics and saying, ‘Oh, so this year, AP tended to have more emphasis on this.’ So I’ll edit.”

Throughout years of teaching countless classes, Ms. Goetz has developed a consistent, signature teaching style. A typical class period is filled with unforgettable mnemonics, corny but well-thought-out math puns and a ton of jokes and banter with her students—she’s like a magician performing tricks before an audience. The way she talks is so energetic and excited that you can’t help but smile. “She comes up with all these mnemonics and things to remember math by,” junior Emily Liu said. “She keeps her lessons fun, because she’s not just droning on. You don’t get bored. She tells a story through math.”

She’ll also try, in a sort of sarcastic self-deprecating way, to make her class laugh in her failed attempts to keep up with teen slang and trends. “Look how hip I am!” she’ll sometimes laugh, pointing out a Bitmoji she inserted in a slide. This year, after the intense 90 seconds of a speed trig, she asked her students to answer “Who rizzed up Livvy Dunne?” on the backs of their paper (the correct answer, “Baby Gronk,” refers to a social media trend that was popular in 2023). She even maintains a YouTube channel with 214 subscribers where she posts her recorded lessons from snow days and the pandemic. Once, a student mentioned that he found a Reddit post by a random internet stranger praising how helpful her videos were.

With such a teaching persona, Ms. Goetz creates a relaxed environment where students feel free to interact with her, interject and laugh while she’s teaching. After she demonstrates the “beauty of math” through a complex proof, she’ll pause and bow at the final step as her students clap and cheer. “Almost every week without fail, the quiet of our class is interrupted by the students of Ms. Goetz’s class clapping and cheering,” freshman Pritish Mukherji said. Mukherji’s AAF class is next door in room 322. “They seem pretty enthusiastic to learn from her.”

When MCPS began implementing smart boards into classrooms in the late 2000s, Ms. Goetz adapted by creating PowerPoint presentations for her lessons. Her quintessential zaniness evolved with it. In her slides, she added animated pictures and spinning emojis, fun and colorful fonts in all-caps and sporadic practice problems she’ll have a student solve—you always have to be on guard because she uses a stack of blue random calling cards. “The number of emojis on her PowerPoints is unbelievable,” Mr. Goetz laughed. “Mr. Davis co-teaches [BC calculus] with her, and he has to edit some of her stuff out because he can’t handle the amount of emojis and things flying in all over the place.” However, most students do find it helpful. “I don’t think they distract from the lesson at all. I enjoy the animations because when you take the test and you see this word, you’ll think of a red arrow popping in,” Martin said.

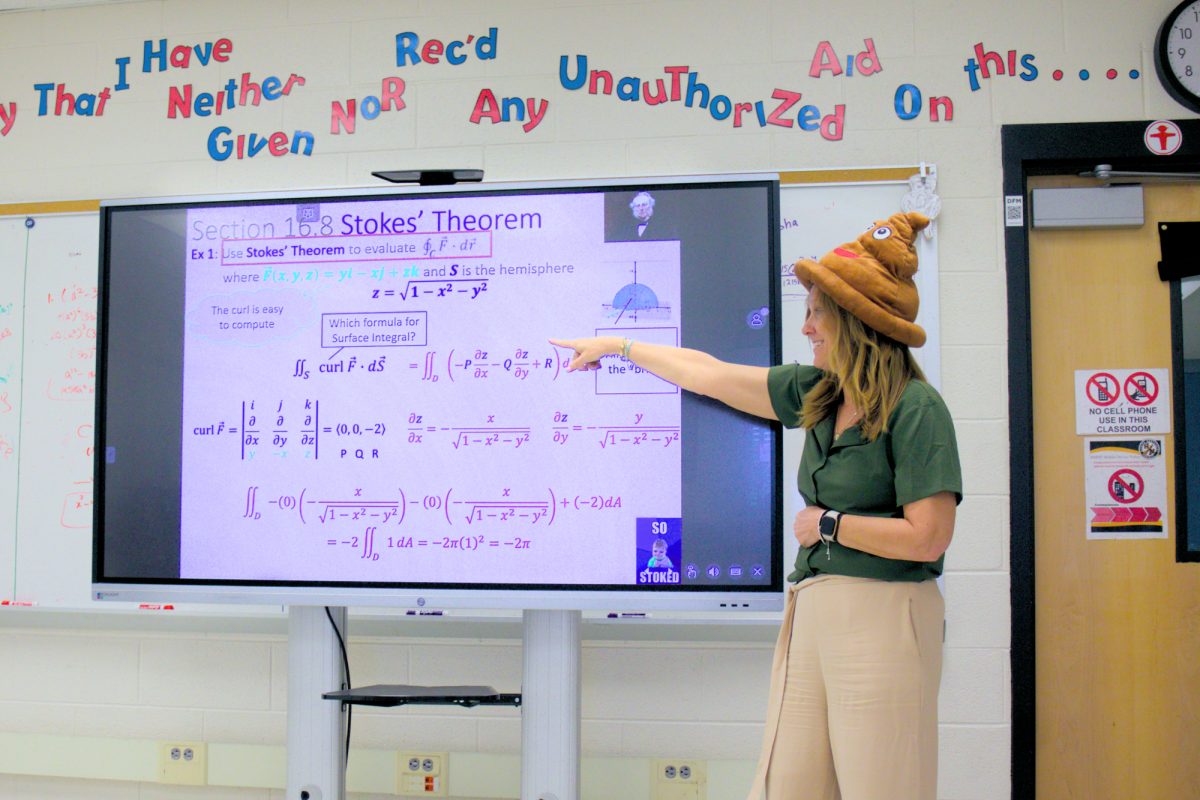

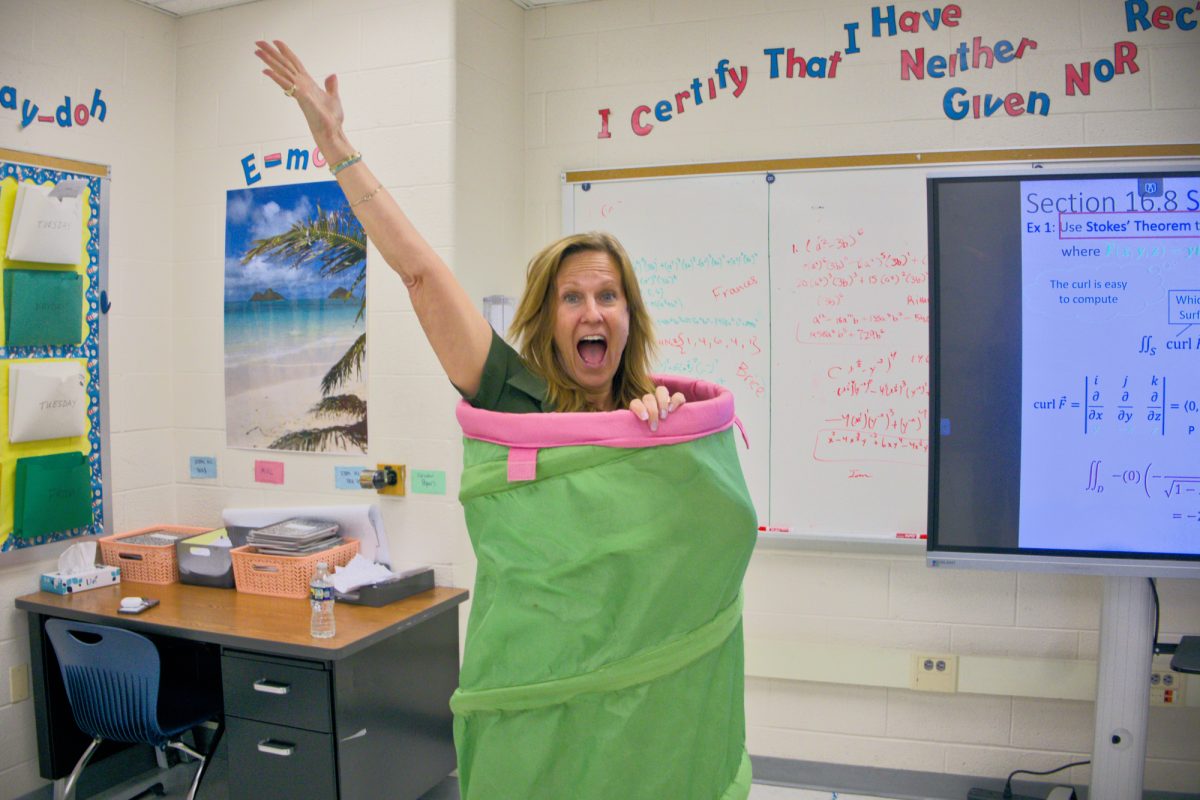

The most unforgettable parts of her lessons are her props and demonstrations. One of her favorites is from the multivariable lesson where she teaches wearing a poop-shaped-hat. “I always do that, teaching Stokes’ theorem. You integrate the curl over the hat or the brim, and you can smush the poop,” she said. In the same course, she transforms herself into a human-sized graph to teach cylindrical coordinates. “When I do cylindrical coordinates in a multivariable graph, I put myself in this big cylinder and they draw on me,” she laughed. “Why not make it fun?”

Ms. Goetz says she acts this way in the classroom to help students break down complex concepts. This has become especially relevant now that she only teaches higher-level math courses. “You’re taking college level classes in high school, and your maturity, your calendar age and your emotional maturity is more than likely not ready for it, but you stretch yourself and you do it anyway,” she said. “But it is hard, and I hope that I can make it easier—and I know [Mr. Goetz] feels the same way—by saying silly things, making the genie come up and jaw drop and just making it seem a little bit less intimidating.”

Of course, at the end of the day, the best part about her as a teacher is just how well she teaches. “Ms. Goetz is a really solid teacher and the way she explains concepts is very easy to grasp. I was able to do well in [HL precalculus] and calculus because she helped me build a very strong foundation,” senior James Zhang said. Ms. Goetz agrees and says that despite her unique teaching style, the most important thing she focuses on is educating her students well. “Mr. Davis and I have been teaching BC calculus together for, God, 15 years. He is the exact opposite of me as a personality in the classroom. He is quiet. He is not loud. He is not going to have Bitmojis or daggers,” she said. “But the kids love him for the same reason they love me. They believe he wants to teach them well.”

To obtain success for her students on rigorous exams, she can sometimes be very harsh—nearly all the students we interviewed called her “tough”—in sharp contrast to her loud and fun demeanor when teaching. She does not give free “filler points” in her course aside from homework, which means that almost all of a student’s grade hinges on non-retakeable assessments. “She’s a tough grader, and she doesn’t take any excuses. She grades harshly and sets really hard deadlines,” Liu said. When we asked Ms. Goetz if she had ever bumped a grade, she simply smiled. “No.”

And while some dislike her harshness, most agree that it ends up benefiting them in the long run. “Some teachers would let you retake things or give you fluff points—things that you’re gonna get 100% on—so you don’t really have to study as much for other tests. But I think what she does is really force you to know what you’re doing, in every part of the material,” Martin said. “She’s not gonna baby you and give you pity points. She’s gonna give you a bad score. So you learn from that and then do better on the next test.”

Regardless of your opinion about her grading, everyone, including Ms. Goetz, agrees that she has strict expectations for students to dedicate time outside school to succeed in her class. “You have time to do your homework. You are only in high school. Even though it’s magnet, you are only in high school. It is not too much,” she said. “It is less than you will be doing in college, so we’re getting you ready for that. I have an expectation that when the bell rings, you will have materials, you will be here, and you have done the practice that I needed you to do the night before.”

Li says that Ms. Goetz worked her students “like dogs” and that now that she’s in college, she has a quarter of the math homework assigned in high school. “It was very helpful because it would be similar to the types of questions she would give us on quizzes and exams. But it was just so much work.” she said. “Sometimes I would be like, ‘Ms. Goetz is actually a crazy woman,’ I remember when we had snow days and then she would email us a recorded lecture to watch and I was like you are so extra. But we were never behind. Say what you will about her methods but they’re effective.”

A lot of Ms. Goetz’s toughness in grading and workload stems from her experience as a struggling single mom in school. “I would get up at 2 a.m. and 3 a.m. and do my schoolwork so that I could be ready in the morning and go take [my kids] to school. Then pass my classes and take my finals. So it’s very hard for me to be empathetic to teenagers here. They say they’re under a lot of stress. They have test anxiety. Do you though?” she scoffed. “I’m quite proud of where I started and how I made it through everything that happened to me, which makes me a little cold-hearted as a teacher.”

But by no means is Ms. Goetz indifferent to students who are struggling—she’ll dedicate time to answer their questions and guide them towards improving. Once, after Wu received a C on a 50-point cumulative exam, Wu went to Ms. Goetz during lunch to ask for help and advice. But before she could get a sentence out, she buckled and started crying uncontrollably under the stress of losing her A in the class. Wu says that Ms. Goetz turned into “Mom Goetz mode” and gave her a comforting pep talk. She ended up staying the entirety of lunch, sobbing and venting while her teacher talked her through it. “By the end of it we did not go over any math, it was just her comforting me. I appreciate that a lot—how she responded with empathy and kindness when she could’ve just said to ‘suck it up.’”

Because of her sympathy and her unique approach, she remains, according to junior Katherine Xue, “a very popular teacher amongst the students” despite her strictness. Both Wu and Li, who are college students, say that Ms. Goetz is their favorite and most memorable high school teacher, and almost all the students we interviewed say that she is among the top. “I know a few people disliked her at the beginning, in the first years of high school, but she grows on everyone,” junior Selena Li said. “It’s hard to not like her after watching her teach enthusiastically for so long, especially since she’s the main teacher for all the upper level classes.”

In RM’s magnet program, which Ms. Goetz teaches, there are two main math pathways. Her classes lie among the higher-level HL pathway, so she has many students who end up dropping down after realizing the even higher workload that awaits them. Yet among those students that we interviewed, she was still heavily lauded—not one complained that she was excessively harsh. Sophomore Marissa Lyons, who took one semester of Ms. Goetz’s HL precalculus and dropped down, still described her as “the best math teacher I’ve ever had by far.” “I was not happy with the grades I was getting. Up until now, I had had straight A’s for years, and it was definitely very discouraging getting bad grades repeatedly,” she said. “The class was hard, but Ms. Goetz is a really good teacher. So if Ms. Goetz wasn’t teaching it, I would have done way worse.”

One of Ms. Goetz’s favorite methods to prepare her students for tests is something that she calls a “little book.” She got the idea from her days as a resource teacher, writing observation reports on her colleagues’ classes. Although she says she hated doing the reports—the process was too stuffy and formal for her—she loved getting inspiration from other classrooms. On one visit, she saw a teacher have her students create a little review book and decided to use it herself. “I get lots of cards and notes from kids, and kids come back from college and are saying, ‘You made a difference. Thank God for your notes. Thank God for your little books,’” she boasted.

As she made this claim to us, one of her former students walked into the classroom—she had seemingly produced him from thin air just to prove her point—to thank her for being one of his favorite teachers. He mentioned how the habit of making little books had especially helped him prepare for college math courses, where professors can’t even recognize your face in a sea of other students. “He’s the third student that I’ve seen this week,” Ms. Goetz grinned. “They’ll often come back and visit, which is really nice.”

The impact she makes on her students certainly is profound. Ms. Goetz shared stories with us about encounters with her past students—at football games, gyms, theaters, museums, happy hours—thanking her for her dedication. Once, she ran into Anthony Williams (who went by Gumby in her class), who is now the head of security at Walter Johnson. During her first years teaching remedial math classes, she developed a close relationship with him. “He was a great kid. He was the star football player. He was the star basketball player,” she said. “He runs across when he sees me, hasn’t seen me in 20 years, and gives me this big bear hug. I made some kind of impact on that person’s life. That’s my favorite.”

Ms. Goetz has almost reached the point where she can retire—she plans to spend her well-earned golden years travelling and passing time with her family in San Diego. But she still may be around to teach the next generation of magnet students—the accident of her career has bloomed into a core part of her identity, and now, she’s hesitant to leave her classroom. “I could walk when I want to walk, but I don’t have any timeline in mind,” she said. “I just will when I will.”

In one of our last interviews, Ms. Goetz rejected the idea of fate. “I believe in chaos theory. Stuff happens that has ripple effects all the way down. And you may never know what the ripple caused. If I decide to drive down this street and I get in a car accident and die, what if I had decided to take that route? You don’t know. But was that really an accident? Was there some driving force that was like, ‘You’re gonna take this road because today’s your day to die?’” she asked. “No. I don’t believe that.”

Her ideas got us thinking: Ironically, her rejection of fate grimly ends up resigning itself to a destiny anyway. If there is no predetermined path to explain and shepherd us through the absurdity of life, where do we find meaning? It can’t be in our actions if our lives are just a series of chances. If so, everything we worry about as fifteen-year-olds in high school—the next unit test in precalculus, making the varsity volleyball team, even the college we attend—would seem trivial. And there’s never an escape from our fate that ultimately, as the passing years approach infinity, we will all be dead and forgotten.

Perhaps, as people like her father believe, our meaning lies in something beyond this world. Then are we all just languishing here on earth in wait for an afterlife whose existence neither Ms. Goetz nor we are sure of? “It’s one of those things I don’t know how much time I need to waste worrying about because I don’t know and I won’t know… But once death happens, there’s no coming back from that,” she said. “I don’t know what happens to me then… but I can’t imagine an afterlife where I’m going to be like, ‘Hey, good to see ya. I remember when we were down on Earth.’” Hearing her, we were both confused. If we never again live fully in any afterlife there may be, meaning for our lives on earth cannot be found in heaven either. Why then, is this amazing woman—permanently in the honeymoon stage of her marriage to life—still so enthusiastic teaching teens math?

She answered us: “I’m going to get everything I can out of my moments here.” That is exactly what sets her apart. In a jaded, cynical world of bare minimums, Ms. Goetz twists and squeezes every last drop out of her life. “There’s going to be sad times, there’s going to be bad times, but I’m going to focus on the good, focus on the love and forgive myself for my mistakes and try to be better. I will fully live out every moment.” There is no contradiction. In Ms. Goetz’s eyes, there is no greater meaning, and we’re all just tiny specks of dust that leave no lasting impact. But that doesn’t matter. In the wake of our insignificance, we must seize the moment anyway, to love, celebrate and be joyful in our lives. For Ms. Goetz, this means doing handstands, wearing poop hats and yelling till she gets red in the face during her lessons. At the end of that conversation, Ms. Goetz smiled widely—you could feel her warmth and her joy and her zeal for life radiating from her. “When I look back, I don’t look back with bitterness,” she said. “It all led to here and I’m proud of myself for going through it and getting through it and for where we—all the people I love—are right now.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Tide, Richard Montgomery High School's student newspaper. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.