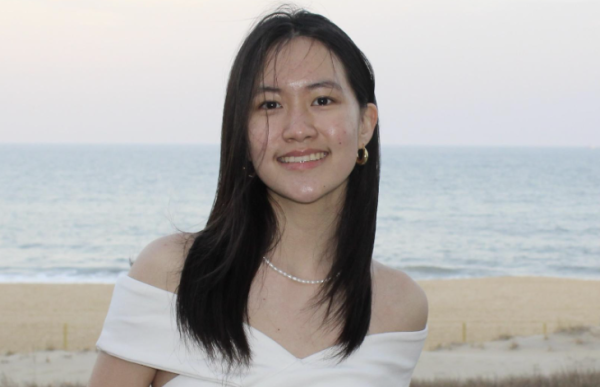

Weapons specialist turned high school chemistry teacher

Photo courtesy of Michael Ashmead

Whenever chemistry teacher Michael Ashmead reveals some aspect of his life, he always manages to astound his students with just how much cooler his life is compared to the average person’s. Ashmead serves as a role model for his students and inspires them to achieve their goals, regardless of how unattainable they may seem.

December 2, 2021

Chemistry teacher Michael Ashmead cheated death five times.

After obtaining his undergraduate degree in chemical engineering at the University of Delaware in 1995, Ashmead was accepted into the Officer Candidate School [OCS], the main training school for aspiring officers in the U.S. Army.

“I’ve had three generations of my family in the military, so I was pretty much already born and raised on a military base,” Ashmead said. “My father kind of pushed me to pursue a career in the military based on my family history.”

He recommends for those interested in going into the Army to take the OCS path because after they obtain a degree, they can automatically apply and be considered for an officer position, which has good compensation and room for developing leadership skills, as officers are put in charge of a battalion.

Due to his exposure to the military from an early age and training during his undergrad, he knew what to expect going in. The physical training was not so grueling for Ashmead, who was prepared for it both physically and mentally. “Once you get used to it, it’s not that bad. The people that find it difficult are the ones that are usually not in shape or prepared for it either physically or mentally,” he said.

Every morning, he and his comrades rose at 4 a.m. for physical training until breakfast, which was usually from 5 to 5:30 a.m. The rest of the day was dedicated to classes and attending meetings. In the military, classes depend on the specialty of the person. Ashmead’s was chemical-based, so his classes were primarily dedicated to chemistry.

“Don’t join the military if you plan on killing people: that’s just stupid,” Ashmead said. “It’s not about going in hoping that you’re going to get into combat, it’s about going in to make yourself better.”

During his time in the military, he worked as a weapons specialist and was stationed in Afghanistan and Iraq throughout the early 2000s. His job was to design, build and manufacture modern weapons.

Ashmead’s experiences used to cause him to have nightmares.“It’s just something you learn to suppress,” he said. “ You learn to control a lot of things in your life.”

The projects Ashmead and his team developed and tested were classified at the time, but the government gradually incorporated them into the military arsenal after they were approved.

Acquiring congressional approval of military budgets proved to be an exasperating task, with some of the report presentations taking hours at a time or even a few days.

“The Senate committees are as dumb as a box of rocks,” Ashmead said. “I’d rather talk to my high school kids because they know more chemistry than the adults do in Congress. It can be very stressful, trying to dumb down advanced technology and research to a bunch of congressmen. It was like teaching them all over again.”

He helped develop and revamp many different kinds of weapons that are still in service today, some of which include drones, the Sidewinder missile and the Tomahawk cruise missiles. The government frequently updates Ashmead on the whereabouts of his weapons.

While in the military, Ashmead was studying for his master’s degree in chemical engineering (Chem-E) at the University of Maryland (UMD.)

His own high school chemistry teacher inspired him to pursue chemistry. “We did this one lab in which it released a lot of heat and from that moment on, I was interested in chemistry,” Ashmead said. “I saw all the great things I can do with chemistry and fell in love with it.”

Although “weapons specialist” was his official title in the military, Ashmead wanted to use chemical engineering to enhance that appellation.

The process to become a chemical engineer was no walk in the park. Classes were stressful, professors were hard to please and lab projects malfunctioned at times. Anything less than a B average, even in core classes, meant academic probation and eventually expulsion from the program if grades were not improved.

“In sophomore year, I focused more on the social part of college,” Ashmead said. “I ended up being on academic probation and I learned real quick when my advisor told me I’m going to fail out of the program. I buckled down and got back on track.”

Quitting was not an option for Ashmead, who had to keep reminding himself to “keep an eye on the prize.”

His hard work and dedication proved worthwhile on graduation day. Ashmead was one of 23 students out of the initial 386 students who finished the Chem-E program.

“My family was there when I walked across the stage and it was probably the best feeling of accomplishment in my entire life and I have no regrets,” Ashmead said. “I was looking forward to starting the next chapter of my life.”

Ashmead already had a job with the Department of Defense, so he knew how that chapter would begin.

Being a weapons specialist for the Department of Defense is very competitive. “When I first went in, I was kind of low on the totem pole, and you’ve got to really work hard to advance your way up to the top to where you want to be. It’s not gonna happen overnight,” Ashmead said.

Once he arrived at the top, Ashmead did everything he could to stay there.

“You can’t get too complacent with the position that you’re in. There’s always somebody below you trying to knock you off the top of the mountain,” Ashmead said.

Being “right” in this position is integral.

“You had to learn how to do a quadruple check of all of your work before it was submitted because I had a lot of people trusting me with my work and my math,” Ashmead said. “If you made a mistake, or if you’ve made multiple mistakes, the trust level was gone, and they would ship you off to another department.”

It took Ashmead eight years, during which he also obtained his second master’s degree in Instructional Systems Design at UMD, to assemble a team of people who trusted one another and were able to take on any projects assigned, which usually entailed altering existing technology to control and neutralize new threats.

The weapons were tested in Fort Hood, Texas.

“That was the fun part about being out in Texas,” Ashmead said. “You’re out standing in the middle of a desert just blowing stuff up—tanks, jeeps, the side of a mountain, everything.”

Unfortunately, being around chemicals for a significant period of time has its repercussions. In 2005, Ashmead was first diagnosed with cancer: he had a tumor in his sinus cavity that was later removed.

In 2009, Ashmead was told that he had nine months to live after he underwent a wisdom tooth removal that revealed a tumor at the base of his tooth. “They stopped the procedure because they saw the tumor,” Ashmead said.

He was diagnosed with stage 3C jaw bone cancer. The roots of the tumor had grown all the way around to the side of his face.

“I researched different cancer centers all around the world and found one in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, and by the time I got there, I was already in stage four, which is like a death sentence,” Ashmead said. “They did this experimental treatment on me where they put me in a hyperbaric chamber for a week and used stem cells to correct the cancer while I was in a drug-induced coma.”

Ashmead woke up five days later and was cancer-free.

The repercussions did not just stop there, though. In 2013, there was an explosion in the lab Ashmead was working in. One of the energy readings was going critical, and Ashmead was responsible for evacuating his team, therefore being the last one out.

“As I was evacuating, my air line in my static suit got caught on one of the lab benches, and the blast door closed. I was trapped and I knew the lab was going to explode,” Ashmead said. His commanding officer told him via phone/intercom call to brace his body up against the wall and close his eyes. “I literally saw my life flash before my eyes, so yes, it is true when people say that.”

The blast from the lab put him into a coma. Ashmead woke up five days later in the medical center.

You’ve got to really work hard to advance your way up to the top to where you want to be. It’s not gonna happen overnight.

— Michael Ashmead

In 2019, Ashmead underwent a procedure to remove a small tumor in his shoulder. Over the years, Ashmead had both shoulders replaced as well and had to relearn how to use both arms all over again.

“I’m mechanical now,” Ashmead said. “I have a little card that says I have metal in me, and when I go through the airport security, I have to show it to them and I just laugh.”

Ashmead applied for early retirement in 2016.

“I learned that there are more important things in life that people must take care of and cherish. Life is too short. Go out and enjoy it,” he said.

2016 was also the year in which Ashmead’s part-time teaching career in Howard County in Fort Meade ended. He had been teaching during the day and working at the military base at night.

In 2017, Ashmead began working at Richard Montgomery High School (RM). He is the current head of the Science National Honor Society and also coaches the men’s varsity tennis team.

The sheer diversity at RM drew Ashmead in.

“It opens your eyes to a lot of cultures, and I love going up and down the hallways and hearing people speak in different languages—it’s culturally satisfying when I hear that,” Ashmead said. “It’s just great to see all the clubs and ethnicities and everything.”

Ashmead has taken up teaching for fun and aims to prepare his students for college and the real world.

“You want to build your independence when you’re in high school because that’s going to help you progress through college,” Ashmead said. “You shouldn’t wait until the last minute. That is the key. Stress is what you make of it.”

Just like his chemistry teacher inspired him, Ashmead continues to have an impact on his students.

“It would honestly be weird if you were in chemistry with Mr. Ashmead and did not once think ‘maybe this could be my career,’” AP Chemistry student and junior Shawn Pourifarsi said. “He manages to break down every single intricacy and detail of chemistry in a way that everyone can understand. From his humor to his stories, Mr. Ashmead as a person is someone I look up to and hope to become.”

Fellow AP Chemistry student and senior Chloe Dondon agrees. “Ever since I was in his class sophomore year, my love for chemistry grew,” Dondon said. “The content is hard sometimes, but I never feel scared to go and ask him questions 100 times. He is actually the reason why I want to pursue chemical engineering in college.”

In eight years’ time, Ashmead plans on retiring fully from his action-packed life and returning back home to Florida. “I plan on fishing on a boat and scuba diving. That’s the rest of my life,” Ashmead said.