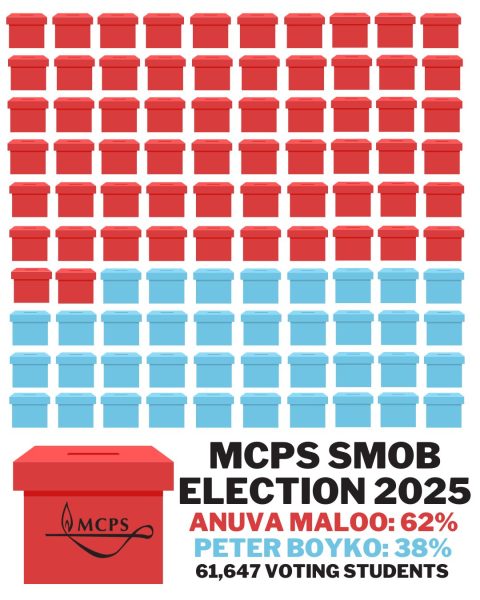

MCPS data reveals student math proficiency plummets

Junior Evelyn Shue studies for a test in the Media Center.

As MCPS students return to school buildings, data presented to the Board of Education in September reveals that students from low-income and minority groups are struggling with math and literacy at higher rates.

A general decline in math proficiency has characterized the student body across all demographic groups, likely in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But these reductions are most pronounced among students in elementary school and at key transition years: second, fifth, eighth and eleventh grade.

In comparison to data from the 2018-2019 school year, proficiency levels for the overall student population have decreased by 35.3 percentage points in second grade, 23.5 percentage points in fifth grade, 10.8 percentage points in eighth grade and 9.2 percentage points in 11th grade.

When analyzed by demographic, data reported in the form of proficiency percentage points representing Black and Hispanic students and students learning English or in special education programs decreased even more compared to the general data.

“I think it’s very hard for MPCS to work through something as massive as [a pandemic] because of how big the system is. This whole system of, like, virtual learning had to be developed kind of on the fly, and enacted for, you know, hundreds of thousands of students and hundreds of schools at all different levels,” math teacher Matt Davis said. “Looking back, I’m not sure what else the system as a whole could have done to make it more effective.”

However, Mr. Davis said that individual teachers did their best to implement small adjustments to their curriculums and teaching styles, as smaller environments were easier to adapt and control in the wake of the pandemic.

“Math especially is a subject where learning new concepts in math is the most successful, I think, when you have a routine,” Mr. Davis said. “It wouldn’t be surprising to me that when you have to go a whole year of school in [a disrupted] format, that people aren’t as successful as they otherwise might have been in … [a] routine.”

“I feel like with math, you study, you study, you study for a test, and then next week, you have to study, study, study for a test. It’s, like, this endless loop,” junior Nani Gildersleeve said. “It’s easy for kids to get burned out– to not do as well on a test and then that, like, really affects their grade.”

In the classes he instructs, Mr. Davis usually assigns a warm-up reviewing content from the day before as a way to assess students’ understanding. If the majority of students are having trouble with the warm-up, he knows to address that before covering new material.

“[But] in the virtual learning … if you had class on like, Monday and Thursday, or Tuesday and Friday … there was like, a lot of time between when we would meet. We only had an hour to like, cover new stuff and see how things were going from the session before,” Mr. Davis said.

Last year, instruction time was dramatically reduced from 45 minutes every day to two hours per week, so students felt they had to independently manage some of their learning. Gildersleeve said that there were times where she received so many assignments in math it felt like she was responsible for teaching herself the material.

According to Mr. Davis, the students who were the most successful last year took advantage of virtual office hours and Wednesday C Days, or arranged for additional meeting times. In a virtual school environment, such opportunities weren’t built into the school day and required asynchronous communication.

Mr. Davis said that simply being back in the classroom with real-time instruction, on a normal schedule, has made a world of difference in teaching and connecting with students. To further mitigate the effects of the pandemic and correct this year’s math proficiency levels, many teachers are offering additional re-teaching opportunities.

“In my perspective, a lot of my math teachers haven’t been sympathetic or anything or empathetic or anything. I’ve had math teachers that didn’t even know my name for the entire year or they never even tried to make those connections,” Gildersleeve said. “The tone that math teachers take toward talking to their students and making them feel valued and like this is a safe space can make such a big difference.”

“It is clear that the pandemic has resulted in a significant learning disruption over the past 18 months,” Interim Superintendent Monifa McKnight told the Bethesda Beat. “This is really going to require … being intentional and direct to know each learner, to know what their learning needs are and address them. That has to happen in every classroom, with every child … in this system. That’s what we owe them.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Tide, Richard Montgomery High School's student newspaper. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.