MCPS student grades have skyrocketed after the grading policy change.

MCPS’ rationale behind grading changes highlights a complex argument

MCPS is a school district embroiled in scandal. Allegations of grade inflation have plagued the county for months, as the semester grading policy that took effect in 2016 has precipitated skyrocketing student grades. An outpouring of concern over the validity of these grades, as seen in a 2018 Washington Post article centered on the rise of As in the MCPS system, has caused the rationale behind the evaluation change to be scrutinized with increasing intensity.

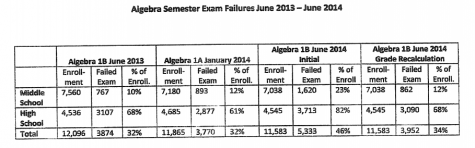

According to an official December 2018 press release, the Board of Education intended to reduce the testing burden on students and increase instructional time in the classroom. These intentions stem from the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College (PARCC) tests, which were first administered during the 2013-2014 school year and were significantly longer than the Maryland High School Assessments (HSAs) they replaced. Students had to sit for four hours on multiple days when taking PARCC tests, and teachers noted the loss of instructional time due to preparing for state assessments like PARCC as a major reason for the increased low and failing grades that appeared in the final examinations of 2014.

“The PARCC exams did not provide us with information fast enough to gain feedback on the students. We want the exam to help teachers but we were not getting measures to see what students were learning until too late,” MCPS Board of Education President Shebra Evans said.

This sharp rise in lower grades prompted the Montgomery County Board of Education to authorize a review of all MCPS assessments and an exploration of options to reduce the testing burden. During this time, the U.S. Department of Education issued new guidelines calling for “fewer and smarter assessments” that are “worth taking, clear in their purpose, high quality, time-limited, fair, fully transparent, just one of multiple measures, and tied to improved student learning.”

As pressure to increase instructional time and revise the final examination policy mounted, MCPS began considering transitioning from semester exams to district quarterly assessments. Feedback from stakeholders such as the Middle School Councils on Teaching and Learning and the Montgomery County Council of PTAs indicated widespread support for this proposal, citing other methods of testing student knowledge and more time for students to review for their assessments as probable beneficial results of implementing the proposed policy.

With these positive responses in mind, the Board eliminated two-hour semester final exams and replaced them with quarterly district assessments in November 2015.

RM alumna Irene Zhou appreciated the elimination of semester exams while in High School, but no longer supports that change now that she is in college. “I’m not totally for the resulting grade inflation. I think it kind of set up some unrealistic expectations for grades in college, and in retrospect it just seems like MoCo is really trying to sweep some important issues under a rug with this kind of inflation,” Zhou said.

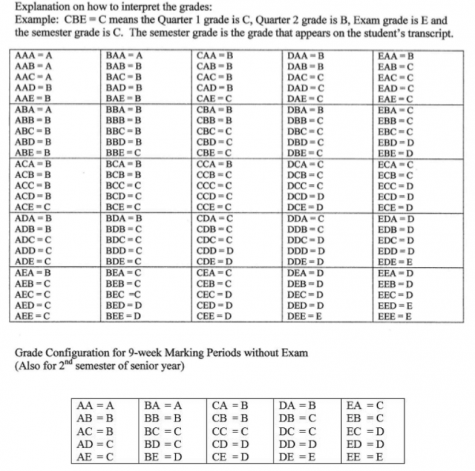

The root cause of the grade inflation Zhou references is the change in MCPS grading policy that the elimination of final exams necessitated. Under the “downward trend” calculation that was in use during late 2015, students’ semester grades were calculated based on the average of both quarters and whether or not the grades reflected a downward trend.

Four alternatives to this system were considered: Numeric (Percent) Average, Quality Point Average, Trend, and an additional “Final Evaluation” Assessment category. Under the percent average plan, final grades would be calculated by averaging marking period percentage grades (MP1 + MP2 / 2). The trend option, on the other hand, was a revised version of the pre-existing downward trend calculation that did not include final exam grades.

Rather than eliminate the final exam category that was weighted at 25 percent, the additional “Final Evaluation” Assessment category option was designed to simply replace the final exam with a teacher-developed “final evaluation” administered in class.

According to an August 8 memorandum from Superintendent Jack Smith to the Board, roughly 300 participants were convened to provide feedback to assess which of the four options resonated most with the MCPS community. These participants included principals, parents, students, and middle and high school teachers, among others. On the whole, most stakeholders felt that the numeric percentage system was overly precise and would precipitate heightened stress and anxiety among students.

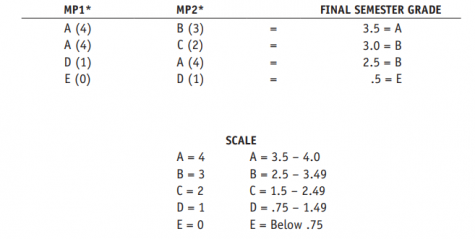

Maintaining the letter grade system of A, B, C, D, or E was also widely supported, as was rejecting the downward trend calculation. Rather than punitively assigning semester grades based on the lowest marks a student received during two quarters, stakeholders preferred using a mathematical “quality point” calculation average. This option entailed calculating final grades by averaging quality points (MP1 + MP2 / 2), with an “A” being worth 4 points, a “B” being worth 3 points, and so on and so forth.

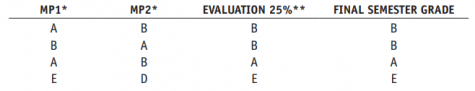

Based on this feedback, MCPS revised the semester grading policy for high school courses by implementing the quality “grade point” calculation average. Beginning in the 2016-2017, high school students began experiencing an academic environment in which they had no more mandated exams to stress over and greater ease acquiring higher semester grades.

Under the old downward trend system, a student who earned an A first quarter, a B second quarter, and a C on their semester exam would receive a B. Now, with the elimination of final exams and the implementation of the “grade point” calculation average, the same student would receive an A.

In a message to the MCPS community released on May 10, 2016, MCPS Interim Superintendent of Schools Larry A. Bowers characterized this new grading calculation as one that: “aligns with standards-based approaches to assessment and college expectations and provides a grading structure that is fair, consistent, and understanding for students and parents.”

In light of the recent grade inflation scandal, however, some students and teachers feel as though the quality calculation average may not actually be as fair as Bowers made it out to be in May 2016.

“I feel like our best students at this school really earn their As. But I think that too many of them, who aren’t strong students, get pushed through and I think that – now I’m going to sound old at this point, like an old timer – but I think when we were kids there was a little more rigor and accuracy to it,” art teacher Mr. McDermott said.

RM alumna Isabelle Zhou, who experienced the change in MCPS grading policy in her junior year of high school, feels differently than Mr. McDermott. “I do believe that the policy was within reason but was also definitely a play to increase grade inflation and the ‘looks’ of the overall system to boost our grade and the prestige of system,” Zhou said.