Your donation will support the student journalists of The Tide, Richard Montgomery High School's student newspaper. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

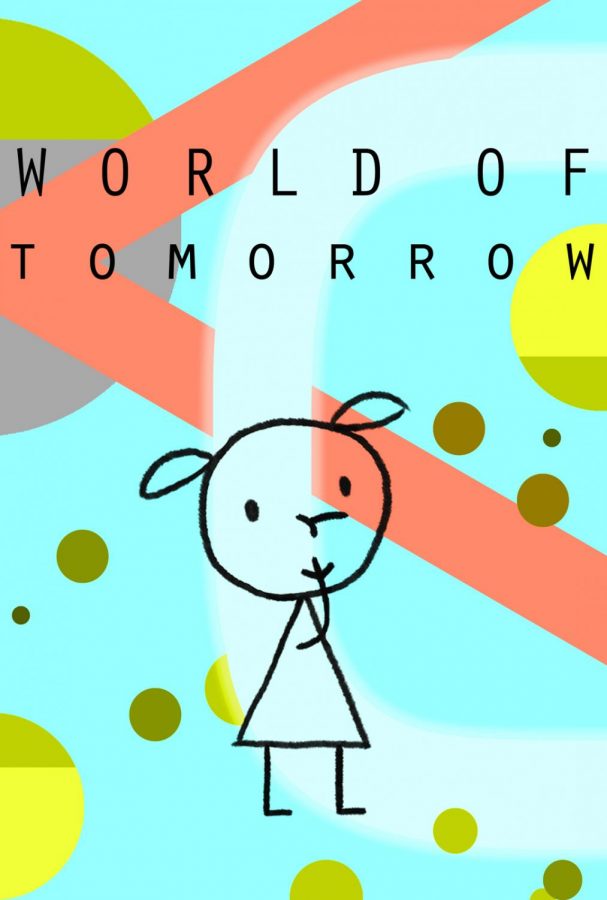

‘World of Tomorrow’: Science fiction that brims with soul

May 19, 2020

Don Hertzfeldt’s 2015 short film “World of Tomorrow,” a story of hope and humanity in the face of inevitable doom, still rings true today.

A staple of early 2000s internet culture, Don Hertzfeldt’s morbid animations—including but not limited to stick figures gawking at giant spoons, anthropomorphic clouds bobbing atop a sea of blood, babies toppling down staircases and unnervingly long wisdom teeth stitches—have collectively reached the epitome of surreal, macabre humor.

But despite the bizarre hilarity of classic shorts like “Rejected” (2000) or “Wisdom Teeth” (2010), Hertzfeldt’s longer projects have historically been a space to poke at larger philosophical beasts. His 2015 animated short film “World of Tomorrow” is no exception: through simple lines and blooming colors, the sci-fi story contemplates everything from our capacity for love to solar-powered robots that fear death. Yet, the focus of “World of Tomorrow” feels anything but scattered. Hertzfeldt effortlessly permeates his apocalyptic dystopia with the beauty of childhood whimsy, and the film’s core message of appreciating the present resounds because of it.

“World of Tomorrow” is a tale of two Emilys, or at least of one toddler-aged Emily and her third generation adult clone from 227 years in the future. In a signature monotone, clone Emily (Julia Pott) hollowly narrates the life she’s lived. Meanwhile, Hertzfeldt’s four-year-old niece Winona Mae voices the original Emily, or “Emily Prime,” in all her unscripted, four-year-old glory—happily burbling about triangles and shooting stars. But those shooting stars are actually dead bodies falling, as clone Emily warns, and the fate of our future world has been sealed by an incoming meteor.

But inevitable doom aside, humanity has otherwise found the key to immortality. Defying death, those who can afford it buy into the unending cycle of uploading memories into clone bodies. People spend their hours staring into screens that digitize and display the memories of past generations—until soon all there is to be seen are past generations staring into the same screens.

While Hertzfeldt makes apt commentary on the screen-centric culture we live in today, as well the disparities of social class (the wealthy brace for the apocalypse by uploading their consciousness into cubes; the poor launch themselves into the atmosphere and become the aforementioned dead bodies), it’s the seemingly silly details of this futuristic world that gives “World of Tomorrow” so much soul.

Clone Emily recounts falling in love with a rock, a fuel pump and a lumpy alien. She describes watching a memory six thousand times over, clinging to a sadness she does not fully comprehend but still chases because the emotion makes her feel human. The absurdity is comedic; it’s something we’d expect from toddlers like Emily Prime. It’s also heartbreaking, profoundly human and hauntingly familiar. Suddenly, we understand.

And perhaps that’s Hertzfeldt’s appeal. Blurring the line of tragedy and comedy, “World of Tomorrow” aches with something universal.