Your donation will support the student journalists of The Tide, Richard Montgomery High School's student newspaper. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

In retrospect: Looking back on the 1918 influenza pandemic

May 14, 2020

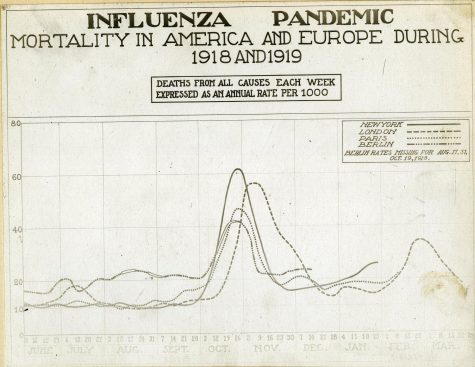

675,000. That is the number of Americans who lost their lives during the 1918 influenza pandemic—a number larger than all U.S. war casualties from World War I to the present day. As the death toll for COVID-19 continues to climb every day, there is no better time to look back on the deadliest disease outbreak in modern history and reflect on what we can learn from it.

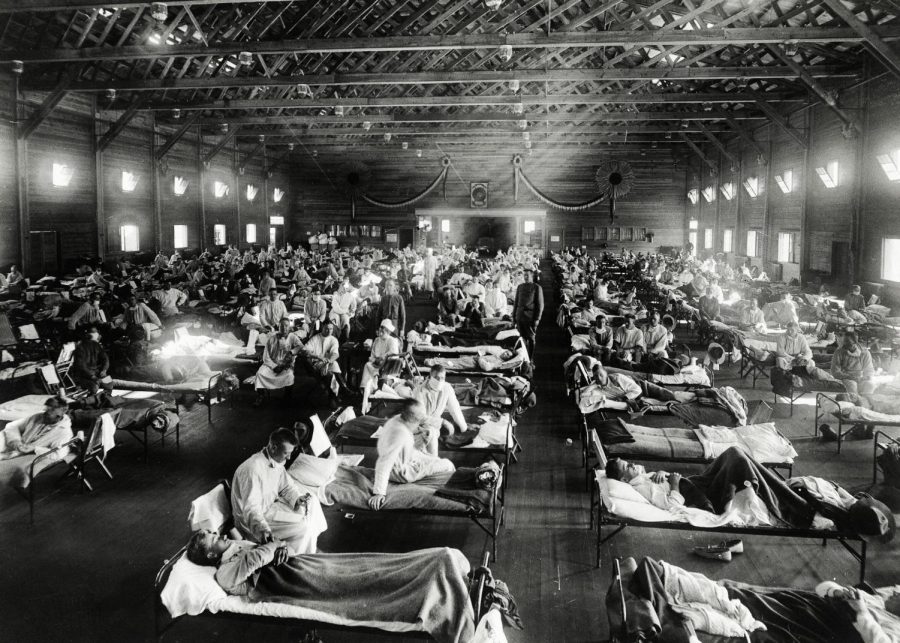

The 1918 flu, also called the Spanish Flu, struck during WWI. Soldiers were deployed across the globe, and with the movement of troops and the crowded conditions in barracks and the trenches, the virus quickly spread. But, as soldiers began to return home during the fall of 1918, the pandemic reached America. Unlike the seasonal flu, where most of the deaths are among the very young and old, the H1N1 virus responsible for the 1918 pandemic claimed many healthy people in the prime of their lives. According to the CDC, the average age of those who died during the pandemic was just 28.

“The 1918 one had a, it’s called a W curve, so it affected the very young, the very old, but then 20-to-40-somethings were hit really hard with this as well. I think that’s a huge difference [from the current pandemic],” history teacher Peter Beach said via a Zoom call. The coronavirus, like the regular flu, has the highest death rate in the elderly.

However, the 1918 H1N1 virus has striking similarities with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in the way that it kills. Many scientists think that the H1N1 virus was so lethal because it triggered something called a cytokine storm, which is essentially an overreaction of the body’s immune system. During this overreaction, the body produces too many immune cells and cytokines, which surge into the lungs to cause severe inflammation and fluid buildup. This process often proves to be fatal, with patients turning blue and suffocating on the fluid filling up their lungs. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines in the blood have also been found in coronavirus patients.

In response to the 1918 pandemic, cities across the U.S. enacted lockdown measures similar to the ones being used today. For example, just two days after the first reported case in St. Louis, the city government closed schools, theaters and churches and banned all public gatherings.

But, not all cities moved as decisively as St. Louis, which ended up having one of the lowest death rates out of all American cities. 10 days after the first case was detected in Philadelphia, city officials still decided to hold a parade to promote the buying of war bonds, which 200,000 people attended. The incubation period of the flu is two to three days, and within 72 hours, all 31 hospitals in Philadelphia were at full capacity. 2,600 people died by the end of the week.

Philadelphia finally imposed restrictions on public gatherings more than 2 weeks after first reported infections. According to a 2007 analysis of the public health measures implemented by different U.S. cities during the pandemic, the peak mortality rate in Philadelphia was more than eight times that of St. Louis.

Like St. Louis, San Francisco was another city that imposed stringent measures in response to the pandemic. On October 18, the city closed schools, theaters and other places of public amusement and banned all social gatherings. Then, with 20,000 cases and more than 1,000 deaths at the end of October, wearing a mask became mandatory under penalty of a fine and jail time. With the war effort still in full swing, California governor William Stephens even told Californians during a public service announcement that it was the “patriotic duty for every American citizen” to wear a mask.

However, the number of new cases in San Francisco seemed to be slowing down. City officials lifted various bans against public gatherings, and the city began to reopen. By November 21, mask-wearing was not required anymore, and at this announcement, San Franciscans tore off their masks and threw them into the streets. “After four weeks of muzzled misery, San Francisco unmasked at noon yesterday and ventured to draw its breath,” the San Francisco Chronicle wrote the next day.

Unfortunately, the flu came roaring back for the city. A second wave of deaths flooded in, and on January 10, 600 new cases were reported for the day. Another 2007 study suggested that had San Francisco kept all its restrictions in place through the spring of 1919, the city could have reduced the number of deaths they experienced by more than 95 percent.

While San Francisco city officials reinstated the mask requirement on January 17, resistance against it came in the form of a group called the Anti-Mask League. Just a week after the new ordinance, 4,500 members of the League gathered to protest against it, claiming that requiring mask-wearing was a violation of the Constitution. Some also questioned the effectiveness of wearing a mask, while others argued that unemployment among the newly-returned soldiers was a larger problem.

“The protests back in 1918 and 1919 were organized. That sort of distrust of experts, distrust of the government’s point of view was very strong,” Bill Issel, professor emeritus of history at San Francisco State University, said during an interview with The Guardian.

These protests draw parallels to the anti-lockdown protests of today, where demonstrators say that the current stay-at-home restrictions violate their civil liberties and unnecessarily hurt the economy. These protests have occurred in many states, including Maryland. On May 2, dozens of Marylanders part of the group Reopen Maryland drove across the state in order to protest the governor’s stay-at-home order. “I didn’t wake up in Communist China and I didn’t wake up in North Korea,” Maryland Rep. Andy Harris told a crowd of protesters at the final stop of the trip.

By the summer of 1919, the influenza pandemic had finally faded. According to the CDC, the pandemic caused the average life expectancy in the U.S. to decline by 12 years. Without vaccines, effective treatments or even much knowledge of viruses themselves—the influenza virus had yet to be identified—people in 1918 had to rely on measures like social distancing and quarantine to slow the spread of the virus. As found by one of the 2007 studies, cities like St. Louis that enacted public health interventions early on had a peak death rate around 50 percent lower than those that did not. However, relaxing restrictions and reopening too early brought on second waves of infection for cities that had otherwise already begun to stabilize.

With the coronavirus today, many states have already started to loosen restrictions. Some states, like Georgia and Texas, have allowed restaurants and other businesses to reopen their doors and welcome in customers again. Looking back at how various cities acted during the 1918 pandemic, the concern that a second wave of COVID-19 infections will arrive is all too real. “Summer is going to come, and we’re going to open back up, and then it’s going to come back with a vengeance in the fall,” Mr. Beach said.