Your donation will support the student journalists of The Tide, Richard Montgomery High School's student newspaper. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

In a sea of war movies, “1917” is forgettable

February 4, 2020

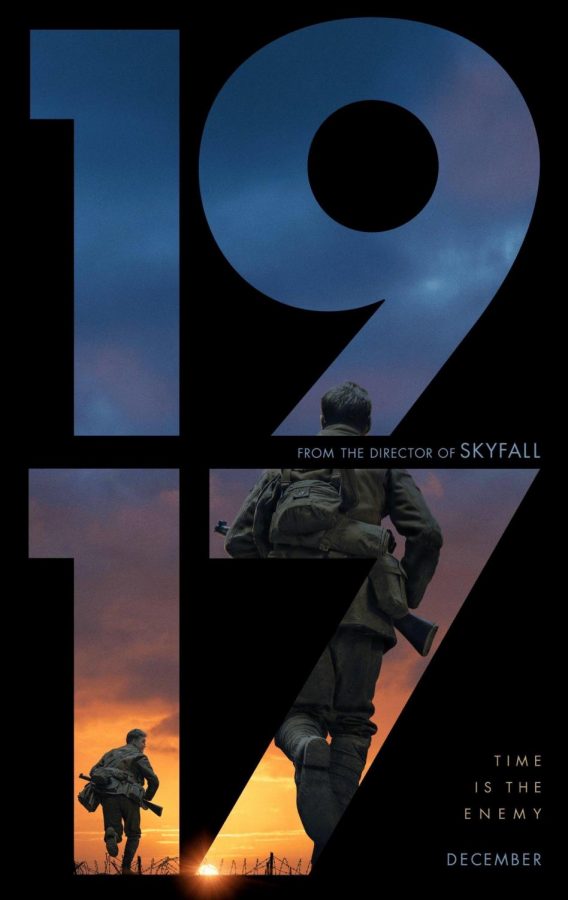

In an industry oversaturated with war movies, mainly about World War II, Sam Mendes’s “1917” offers a breath of fresh air by shining a light on the neglected Great War. While the film may be a masterful work of cinematography, it is plagued by an empty plot, little character development, and few themes.

From the trailer, I originally assumed “1917” would be a typical war movie; the grand music, explosions, and a ticking clock in the background all pointed towards an action-packed and exciting film. Surprisingly, the film takes a more emotional slant emphasizing personal struggles as opposed to all-out conflict. The audience follows Lance Corporals Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield (George Mackay) on their journey through Northern France and deep into German territory to deliver orders which would save 1,600 Allied lives.

Quietly opening the story, the camera gracefully pans down to show barely adult Lance Corporals Blake and Schofield napping near a tree next to a serene field and distant forest. Suddenly, the two are woken by another soldier who leads them through the British camp and into the trenches to meet with General Erinmore. Immediately, the stark contrast between the beauty of Northern Europe and the rat-infested military camps conveys the before-and-after effects of the conflict on nature, establishing the tone of the movie.

Entering a small, dimly lit bunker, the general informs the two men of the planned British invasion past the Hindenburg line that, unbeknown to the troops, is to be met by a German ambush. Along with the information that Blake’s brother is among those troops, the two men learn that they must venture through no-man’s-land and deliver a message calling off the attack. Aided by the masterful use of a droning sound and dim candlelight, the film creates atmospheric anxiety that lasts till the end of the film.

Determined to save their countrymen, Blake and Schofield salute their superiors and walk out into the daylight with the camera following behind. The long, immersive and uninterrupted shots underscored the impressive cinematography of “1917”. After I became accustomed to the filming style, I began to appreciate how the audience became part of the story, as if the camera was a fellow soldier moving through puddles, running through battlefields, and almost drowning in rivers along with the main two protagonists.

From this intensity, the movie never develops the characters’ backstories. Although the two occasionally speak of their lives before the war and mention their families, a majority of the movie consists of long sequences of hiding behind objects and darting for safety, less substantial than meaningful dialogue.

The second part of the movie picks up the pace and emotion, emphasizing the terrible nature of war by introducing noncombatants, or civilians, and horrifically beautiful scenes of French villages on fire. All the tension that had been created throughout the film was released on the battlefield as Schofield runs through the barrage of German shells, colliding with other British soldiers in desperation to get the message to Colonel MacKenzie. Unfortunately, only at the end of the movie does the audience finally get their first taste of character complexity from Schofield as he struggles with fear and his will to fight and save people.

The entire film tries to play on the concept of simple but impressive, yet the movie treads on the side of being a little too simple. Although the plot was meant to span over a brief time and show how times of war can be silent and not filled with bloodshed, Mendes’s effort in creating a movie of that design led to him eliminating too much of the storyline. This lack of detail distances the audience from the movie, contradictory to the camera style, which ultimately makes “1917” forgettable.

Despite this, “1917” is an overall great film that provides WW1 a counterpart to movies like “Saving Private Ryan”. Even though Mendes could have set aside some of the almost two-hour runtime to more traditional development, his main goal of presenting the more behind-the-scenes aspects of war is absolutely accomplished.